Established April 14, 1942

|

American Ex-Prisoners of War

A not-for-profit, Congressionally-chartered veterans’ service organization advocating for former prisoners of war and their families.

Established April 14, 1942 |

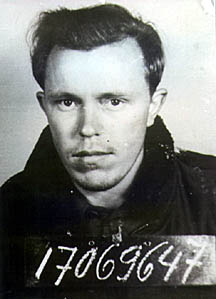

Charles Lyon as a POW

|

Charlie and Mary Jo at Memorial dedicated to KIA crew members

|

Charlie and the Farmer's Daughters in 1965 in Italy

|

| Last Name | First Name, Middle Init. | Nickname |

| Spouse | City | State, Zip |

| Conflict — Theatre | Branch of Service | Unit: |

| Military Job | Date Captured | Where Captured |

| Age at Capture | Time Interned | Camps |

| Date Liberated | Medals Received | |

| After the War ... | ||

The Anthon, Iowa native whose B-17 Flying Fortress was shot down in the Italian Alps during World War II returned with his wife to the crash site where four of his 10-man crew perished. Not only did the natives of the small Italian village of St. Leonhard grandly host him and Mary Jo, they made them guests of honor at the dedication of two memorials to American airmen who died nearby while fighting against Italy and its German allies.

One memorial was to honor those from Lyon's 301st Bomb Group, who died near St. Leonhard on December 29, 1944. The second was dedicated to the 12 crew members of a B-24 who died when their aircraft was shot down a couple of miles away near St. Andrea on February 28, 1945. That dedication was at Brixen, a larger town near the crash sites.

Lyon, 76, was amazed at the generosity of spirit the people of the region demonstrated. "Maybe it's not unprecedented, to put up monuments to the enemy dead, but they have their own dead," he mused.

However, the downing of Lyon's particular B-17 is a story with several unusual circumstances. "We got a direct hit, and I knew we were going down," Lyon recalled. "I was trying to get to the door to bail out when the plane exploded." Lyon, a waist gunner, regained consciousness in mid-air and opened his parachute.

His navigator, Arthur Frechette, was not quite so lucky -- or maybe he was luckier. He slammed into the steep side of a snow-covered mountain seconds after regaining consciousness with no parachute. He survived his injuries and, in time, went on to a long career teaching mathematics in Connecticut, where he still resides.

Even with that, the crew's luck had not run out. Lyon's co-pilot, Sam Wheeler, was blown out of the plane at 25,000 feet without a parachute. As he was falling he was struck in the face by a loose object which he grabbed reflexively and which turned out to be a parachute. He quickly donned the captured chute and pulled the ripcord. It belonged to Frechette. The event was recorded in the Stars and Stripes of the day as "one of the more unusual" occurrences of the war, Lyon recalled. In addition to the recent formalities in Italy, Lyon was able to meet casually with the son and three daughters of the farmer who had rescued him.

Josef Frener had gone to look for Lyon three times that day, and finally located him just before dark, stuck in a tree and bleeding from minor injuries. Lyon said Frener saved his life, given the deadly mountain weather. After ensuring Lyon was unarmed, Frener took him to his home, gave him a hearty meal and a featherbed to sleep in. Lyon in turn gave the little girls pieces of chocolate from his survival kit.

The next morning Lyon helped Frau Frener churn butter, hoping to garner her favor and thus her aid in getting to nearby Austria where he would be safe. His effort had no effect. Soon German soldiers came, taking him to the prison camp at Nuremberg.

But the three girls, now middle-aged adults, remembered "the handsome American airman" and his chocolate. Through an interpreter they told Lyon that they were the envy of every girl in school after the bomber was shot down. Their mother made silk dresses for them from the remnants of his parachute.

Lyon had stayed only three months at Nuremberg when he was sent on a forced march to another camp about 100 miles south, near Munich. There the Germans had hoped to negotiate with their American prisoners.

In 1965 Charlie took Mary Jo and their family to visit Germany. "I'd kept a diary on the march; I kept track of every place I'd slept," Lyon said. On his return trip, following his diary, they found every spot. On that same trip, the Lyons were befriended by a German, Martin Braun, who, with a knowledge of English, helped them negotiate the countryside. Braun, a former enemy soldier, subsequently made 16 trips to the United States, visiting the Lyons. "He was in anti-aircraft" Lyon said. "We always kidded that he shot my plane down. He said, no, they never could hit anything," Lyon recounted, laughing.

Touched by the 1965 trip, Lyons' son Tim, then 45, made an individual pilgrimage to the crash site in 1971 when he graduated from high school. He now runs the family bee-keeping business in Herrick, S.D. a third-generation apiarist.

And so in the fullness of time, in 1998, Charlie Lyon had gone from being a prisoner in enemy territory to being among the first Americans ever entertained by officials of Brixen town going back to its founding 901 AD. Both Airmen monuments were blessed by the Church, a requirement in Italy, then set on footings at the rural sites.

And Lyon, who once again found the exact spot of his plane's crash, brought back a lot of memories and a small bag filled with pieces of rust-encrusted metal. "It's just a bunch of junk," he explained, "but to me it's history."