|

American Ex-Prisoners of War

A not-for-profit, Congressionally-chartered veterans’ service organization advocating for former prisoners of war and their families.

Established April 14, 1942. |

Partner WebsitesAXPOW has official ties with several organizations which share our mission of maintaining and promoting the values, traditions and heritage embodied in the military veterans who dedicated their lives to protecting and defending our country's way of life in times of war.

These groups, like ours, are committed to keeping those values, and their stories, alive for the edification of future generations. Their websites should be of significant interest to readers of this site for many of the same reasons ours is. NAM-POWs, Inc.: Andersonville National Historic Site: comprises the former site of Camp Sumter military prison, the Andersonville National Cemetery, and the National Prisoner of War Museum, which honors all U.S. POWs in all wars. Its National Cemetery has been used continuously since its founding and currently averages over 150 burials a year. Friends of Andersonville: works with the National Park site to broaden understanding of the role played by one of the largest Confederate compounds to hold Union captives during a tragic period in American history.

As a 501(3)c nonprofit organization, American Ex-Prisoners of War is eligible to receive tax-deductible charitable contributions. GuideStar gathers, organizes, and distributes information about U.S nonprofits, and awards its gold seal in recognition of transparency and currency in financial reporting.

|

Five Christmases, Many Years Ago.Christmastime during war years can be a melancholy time. Anxiety over the fate and fortunes of loved ones fighting in foreign lands, fears about an uncertain future both at home and abroad and the steady toll of isolation and scarcity borne of a war-time economy canl suck the joy out of daily living and make it exhausting to try to summon the enthusiasms attendant to a joyous holiday season. But when the armistice is finally signed, that year’s Christmas generally sends spirits soaring. Just as the bible promises that joy will come in the morning after the long, dark night. Most of the time. Christmas 1945

World War II ended for good with the surrender of Japan in September 1945, following Germany’s earlier capitulation in May of that year. That left barely enough time to summon up the full measure of requisite joy, relief and thanksgiving in time for Christmas. Tears were shed for the nation’s losses, the prayers of remembrance and gratitude took time to gather their full voice, and then the once-familiar pace of life shortly began to return. And the troops would be mostly home by the holidays.

Christmas 1945 promised to be the Greatest Celebration in American History. President Truman declared a four-day Christmas weekend for federal employees. The U.S. Military launched Operation Magic Carpet to repatriate tens of thousands of GI's in Europe and Asia to their homes for Christmas, and both the Army and Navy launched Operation Santa Claus, to process the discharges of thousands of armed forces members before the big day. Stores and churches both were filled to capacity leading up to the Christmas season of 1945. After years of separations and deprivations, a war-weary nation was humbled in gratitude and bursting in celebration that it at long last, finally, was all over. Rail depots, bus stations and airports were clogged with returning troops and born-again civilian travelers, creating what was for then the biggest traffic jam in the nation's history. Some sailors and soldiers stuck on the roads en route were driven thousands of miles home by grateful citizens consumed in the warmth of Christmas spirit. Cities and towns, big and small, were caught up in an outpouring of love and good will worthy of of the best of the American character. With the end of World War II, the US would experience one of the greatest economic expansions in history. The war effort had helped pull the country out of the Great Depression, with the government investing billions of dollars in manufacturing and other industries. The unemployment rate dropped from 14.6% in 1940 to 1.2% in 1944. In 1945, defense spending made up about 40% of the nation's GDP. After the war ended, however, the government cut military contracts and returning soldiers were competing with civilians for jobs. The economy entered a recession, with GDP contracting by 11%, but prosperity recovered quickly. The US would grow in peace time into the world's largest industrial economy. A future so bright: gotta wear shades. Christmas 1865

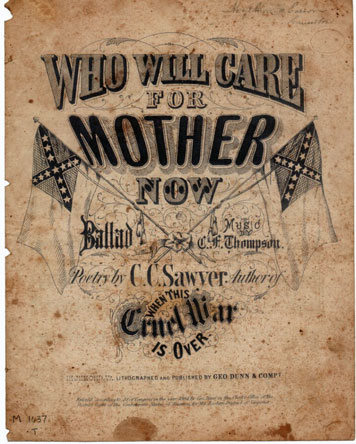

The end of the War Between the States brought forth a deep nationwide sigh of relief, but it also brought a peace that was far different from that emanating from other wars. It was a war half of the country had fought and lost. Approximately 750,000 died in the war, which still owns the distinction of being the bloodiest in American history. Imagine what that number translated into, in terms of sons killed, families changed, members turned against one another. For war wives and widows, the holidays would be an exceptionally emotional time. The absence of loved ones, both temporary and forever; the enduring reminders of streets and buildings draped in crepe; the troops marching through towns; mourning neighbors attired in black; scarce food and provisions; and new-found poverty for too many must have made that first Christmas particularly painful. But the Christmas of 1865 served a salutary effect in one way. The holidays were embraced by millions as a way to begin the process of reuniting the country. The recreation of an American Christmas was a response to social and personal needs that arose following a time of intense sectional conflict. New and newly adopted customs and meanings managed to help the nation make sense of the confusions of the era and to enjoy, if only for a brief period of time each year, a soothing feeling of unity. Before the Civil War, Christmas was not an official holiday in the United States. Nor was it celebrated uniformly across the country. Many Americans, churched or unchurched, northerners or southerners, had hardly taken notice of

The upheaval of the Civil War made Christmas seem more and more important to many. “The Christmas season [reminded] mid-19th century Americans of the importance of home and its associations, of invented traditions,” wrote historian David Anderson. With the war ended, magazines and newspapers that had underlined the importance of the holiday kept promoting it. Families, devastated by the losses of the war, began to cherish the optimism and wholesomeness of the holiday. In 1870, Congress passed the first federal holiday law making Christmas an official holiday. Four years of the deprivations and personal loss of war contributed to changing the holiday from a casual or even ignored calendar event into an essential family celebration. (footnote: Three weeks before Christmas, the 13th Amendment—the first of the three Reconstruction Amendments—was ratified on December 6, 1865, forbidding chattel slavery across the United States and its territories. The nation, no longer divided, celebrated for the first time a new birth of freedom in the land.) Christmas 1953

Korea wasn’t even a war, and what’s more it never ended. None was ever declared, and no peace treaty was ever signed. But it was war enough to the nearly 40,000 American troops who gave their lives. And the nearly 4,000 prisoners of war who sacrificed their time and freedom for the national good. On December 24 in Washington, D.C., President Dwight D. Eisenhower lit the National Community Christmas Tree, a 30-foot Oriental spruce decorated with 1,500 bulbs and illuminated by mercury vapor floodlights. The ceremony was broadcast on the radio and television. He thanked God for the peaceful season, the nation’s first since 1949. The song "Santa Baby," sung by Eartha Kitt, was the best-selling Christmas song of 1953 in the United States. It also found success in Canada, France, Germany, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

1953 National Christmas Tree lighting

National Archives and Records Administration

While it never touched our shores and at times barely entered our consciousness in comparison with other wars, the Korean War significantly impacted domestic life in the US just the same. It boosted the economy through increased military spending, which eventually led to inflation and higher taxes. The Korean War's effect on domestic politics in the United States was reflected in the loss of public trust in President Truman because of his decisions to declare war on North Korea without the consent of Congress and to fire General Douglas MacArthur as commander of United Nations forces. It also fueled the "Red Scare" with heightened anti-communist sentiment. Ultimately, through frustration and stalemate, it likely contributed to the election of Dwight D. Eisenhower as president in 1952. Christmas 1918

By rights, Christmas 1918 should have been the merriest of Yuletides. The "Great War" had finally come to an end, with an armistice signed just one month before the holiday. Many of the boys would be home in time to join the celebrations. But they would be bringing a deadly illness with them. The whole world was in the grasp of an influenza pandemic, and the Christmas season that year fell between two waves of the outbreak. The "Spanish flu," one of the deadliest pandemics in human history, raged worldwide between 1918 and 1919. An estimated 500 million people caught it, about one-third of the world’s population, and it killed more people than the Black Plague did in the 14th century. The celebrations went forward, sometimes too rashly and precipitously. It was an unfortunate time for people to want to mingle together in large numbers.. The saga of the Spanish Flu epidemic overshadowed another, less-told Christmas story from 1918. The New York Times recounts the story in a December 25, 2019 article that when the German delegates signed the Armistice papers on Nov. 11, 1918, they asked the Allies to lift a blockade that was causing rampant starvation in Germany. It was maintained primarily by Britain and overseen by a multilateral group called the Inter-Allied Blockade Council. Civilians in Germany were hungry, and the flu had killed many. The Allies agreed to “contemplate the provisioning of Germany,” but would not agree to lift the blockade at that time. By late December, with Christmas approaching, — foreign food was still not making its way into Germany. The final peace had not yet been signed, and some Allied leaders feared that the Germans could start fighting again. Better to keep the pressure on.

The Times reports that President Woodrow Wilson sent a letter to the other Allied leaders on Dec. 15, urging them to lift the blockade and allow neutral countries to bring food to the German public. Herbert Hoover, then in charge of American food aid to Europe, had devised a scheme to export pork to Scandinavia. There were no legal restrictions against re-exporting to Germany.

On Christmas Eve, the Allied governments approved Wilson’s request through the blockade council. On Christmas Day Hoover wrote to Ira Morris, America's ambassador to Sweden, with the news.

It seemed, finally, that the two sides, still technically at war, could overcome their distrust with their common sense of humanity. But in fact, it did not happen. Within days, the European allies rejected the idea and canceled the agreement. The exact reasons are unknown, but it is easy to surmise that some of the allied governments remained too embittered by war to see the enemy, even children and civilians, as anything but the enemy. That same seeming desire, to punish the German citizenry, would later, in the minds of many, infuse the Treaty of Versailles itself. (Thereby planting the seeds of resentment that would push Germany down the path to World War II?)

Untold thousands of Germans died of starvation that winter, who could have lived had Wilson and Hoover prevailed. The blockade on foodstuffs remained in place until July 12, 1919, following the signing of the Versailles treaty.

If the renowned Christmas truce of 1914, so often extolled as exemplifying the finest instincts of humanity in time of war, can teach us anything about the importance of yielding to our inbred revulsion of war, the Christmas blockade of 1918 teaches how hard a gesture that can be when enveloped in the fog of war, especially when it requires forgiveness — perhaps, the Times reporter muses, of all the gestures encompassed within the human psyche, the most beautiful to receive but the most difficult to extend.

The Civil War (1861-1865) and the two World Wars (1914-1919 and 1939-1945 respectively) seemed to invade every aspect of our nation's daily affairs. The Korean War far less so; daily life often seemed to go on around it. The Vietnam War (1955 to 1975) went on for 20 years. For much of that duration, daily life at home went on almost oblivious to it. Until at length frustration with it succeeded in fracturing American society.

No one could win it; no one seemed able to end it. In time, almost everyone turned against it, for varying— sometimes even opposing—reasons, even though it began for, in the eyes of most, the seemingly noblest of reasons. But long after we got tired of it, we still couldn't stop fighting it. And even when it was really ending, we still almost couldn't make it. President Richard Nixon must be credited with bringing hostilities to a close, albeit with a violently hostile act.

American forces had stopped fighting in the Vietnam War by March 1973 when the Treaty of Paris was signed and the last combat troops left South Vietnam. While that marked the end of direct US military involvement, North Vietnam continued fighting what became a civil war against the South that ended with the fall of Saigon in 1975.

Students of the war could wryly claim that Christmas came early in 1975. The holiday-favorite song "White Christmas" was used as a coded signal to initiate the evacuation of Americans who were still in Saigon in April of that year

(some 5,000 in number including diplomats, contractors, marine guards, and CIA employees).

Armed Forces Radio played the song over and over to indicate that the evacuation, known as "Operation Frequent Wind," was underway; essentially, Americans serving “in country” had been instructed that the playing of "White Christmas" meant the fall of Saigon was imminent, and it was time to leave, which everyone who could did with all due swiftness. And some degree of panic.

When the hostilities had ceased in 1973, just barely past Christmas, the moment was generally met with relief and a sense of quiet celebration among Americans, particularly families with loved ones who would be returning home from service. However, the "Christmas Bombing" of North Vietnam that was carried out right before Christmas 1972, lent a particularly somber feeling for many due to the heavy civilian casualties involved and the shattered hopes that they might be reunited with their loved ones in time for the holidays. Sadly, at its roots all war is personal.

On December 18, President Nixon had ordered a massive bombing campaign of Hanoi and Haiphong, code named Linebacker II. It reportedly killed more than 1,500 Vietnamese. By late 1972, U.S. combat involvement in Vietnam had already been dramatically reduced, and protracted negotiations to end the war were well underway.

When those negotiations broke down on December 16, Nixon issued an ultimatum for the North to return to negotiations within 72 hours, after which he ordered the bombing campaign. The effect of the bombings on negotiations is still debated by chroniclers, but on December 22, when Nixon again asked the North to return to the talks with the terms offered the preceding October, they acceded. On January 27, 1973, the Paris Peace Accords would be signed along the same terms as that October agreement.

B52s and their crews stood alert for seven days a month. Wives, girlfriends, and families had visiting privileges at the air force Base when their men were on active duty, and one Sunday evening in May I went out to visit. It didn’t go as either of us had expected. Robert had been informed earlier in the day that all planes would be leaving for Guam by the end of the following week. So, I could marry Robert by the week’s end or wait for his return in six months

We were wed on May 25, 1972. As luck would have it, we wound up with six whole weeks of married life together before he left for Guam. We communicated after that daily by letter. We had two phone calls in six months. Phone calls to Guam were six dollars a minute at the time!

I kept busy teaching two sessions of kindergarten daily and teaching community college two nights a week. Robert was due home the first week in December, but his orders were cancelled. The new date of return was December 18.

I was so excited. I decorated the house with a tree and a manger scene he had made in the base hobby shop, as he liked to say, “between bombing runs.” A Colonel had brought it to me in mid-December. Life was looking up.

But when December 18 came, my world changed very unexpectedly. No matter how steady and solid you think you are, no one is prepared for the arrival of a notification of wartime status of a loved one.

It was Christmas break, and I was having lunch with my parents. I had planned to pick Robert up in the morning hours of December 19. My mother answered the phone Sometime earlier, a pilot’s wife had told me to never worry until the white-top cars show up. Well, two white- top cars were sitting outside our front door with at least six officers inside. This was my worst nightmare coming true.

My mother and father had their arms around me as the notifying officer read a letter explaining that Robert had been shot down over Hanoi and was classified as Missing in Action. I didn’t know that B52s were flying over North Vietnam. Robert had not warned me that he would not be home on the 18th although he was suspicious with all the activities going on in Guam. The whole world exploded, for me and other family members.

The visiting officers expressed their sympathies. I was going to go lie down when the phone rang again. Robert's Social Security number was being released by Radio Hanoi. The next morning Robert’s picture, along with those of five other officers, was published around the world in every major newspaper. We were all learning about the United States attack on Hanoi.

This was the beginning of Linebacker II. The bombing runs lasted for 11 days. My husband just happened to be on the first airplane to go down over Hanoi and was the first one captured.

I had no idea when he would be home. My job was to go on with my life, as a schoolteacher and as a wife with a husband in the “Hanoi Hilton.” But all my sights were set all along on the day my Robert would come back home to me.

A peace treaty was signed in January, and life was looking hopeful. We were informed each time a group of men was being flown home. I would be notified that Robert was or was not on the airplane. But by the second release I'd figured out that the last ones in were going to be the last ones out. It was fair, but each time I got the same discouraging message, my stomach would tie itself up in knots.

And indeed, Robert was on the last plane to leave Hanoi. On March 29. He called me when he reached the Philippines. Christmas could wait for one more year.

posted 12/7/24

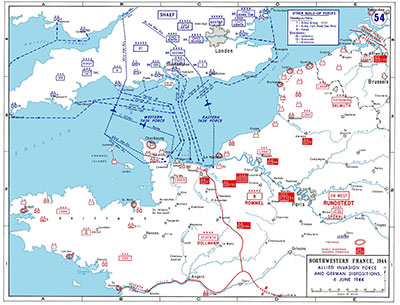

The program for the week of events across a 50-mile stretch of beaches runs more than 30 pages — with concerts, parades, parachute drops, convoys and ceremonies. President Emmanuel Macron of France is presiding over eight commemorations in three days. Two dozen heads of state are expected, including the Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky. On Monday Parachutists jumped from World War II-era planes into now peaceful Normandy to kick off a week of ceremonies marking the 80th anniversary of D-Day The Anniversary celebration’s centerpiece will be a ceremony June 6 attended by President Joe Biden, his French counterpart, Emmanuel Macron, Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Britain’s Prince William and other world leaders. President Biden will give a speech about defending freedom and democracy. Get up early June 6 and be a part of history. Sky News will provide a live stream of the June 6 80th Anniversary activities. You can join in on the link below (on YouTube) on June 6 starting at 6:30 a.m. The feed is already streaming selected activities if you want to tune in earlier Feel free to look around.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4diy4CsXknY

The Normandy American Cemetery, sited on a bluff high above the north coast of France, is one of the world’s best-known military memorials. The World War II cemetery there contains the graves of nearly 9,400 war dead, with nearly 1,600 names on its Walls of the Missing, names of men most of whom lost their lives in the D-Day landings and ensuing operations. Its hallowed grounds preserve the remains of nearly 9,400 Americans who died during the Allied liberation of France. Three Medal of Honor recipients rest here. Forty-five sets of brothers lie side by side. The visitor center describes the events and significance of the D-Day landings and the ensuing campaign for Normandy. Every year over a million visitors come to pay their respects to the fallen and learn more about the crucial events that happened here. Within the picturesque trees, an immense array of headstones rises in long regular rows. At the west end of the cemetery, granite statues represent the United States and France. A small chapel sits at the center of the cemetery. Inside, a ceiling mosaic depicts America blessing her sons as they depart to fight for freedom. In the open arc of the memorial, a bronze statue symbolizes the indomitable spirit of American youth. Over 1,500 names are carved on the walls in the Garden of the Missing behind the memorial. The daunting challenges and intense combat of the campaigns to liberate France live on in this inspiring burial ground – the final resting place for so many courageous American servicemen and women.

posted 6/5/24

Veterans and Military Connected Community

White House Office of Public Engagement April 9, 2024 A Proclamation on National Former Prisoner of War Recognition Day

2024 On this day, we honor the more than half a million brave patriots who sacrificed their freedom as prisoners of war — risking their own safety for the safety of their fellow Americans. We recommit to fulfilling our country’s one truly sacred obligation: to prepare and equip those we send into harm’s way and to care for them and their families when they return home and when they do not.

>p>Last September, I visited a memorial in Hanoi for my friend, former United States Senator John McCain, who had been imprisoned there for five and a half years when he was a Lieutenant Commander in the Navy. I reflected on the unfathomable conditions and pain that he and so many others have endured as prisoners of war. It was a solemn reminder of the grave costs of war and the immense sacrifices American service members are willing to make to defend our Nation. They have always embodied the highest expectations of our democracy — daring all and risking all so that our country remains free and our people remain safe. We owe them and their families, caregivers, and survivors a debt of gratitude we can never fully repay but will never cease trying to fulfill.

Today, and every day, we recommit to this vow. We honor the unbending courage and unshakable devotion of our former prisoners of war. We reaffirm our commitment to bringing home all those still missing or unaccounted for. We pledge to keep faith in all these heroes and their families — just as they have kept ultimate faith in our Nation. May God bless our former prisoners of war and their families, caregivers, and survivors — and may God protect our troops. Click here to read the full proclamation. Remembering Our Veterans This Christmas PastOn a December morning back in 2008, six Christmas wreaths showed up in a package addressed to the Andersonville National Cemetery (a principal component of the Andersonville National Historic Site in southern Georgia, which also encompasses the National Prisoner of War Museum and the Confederacy's historic and infamous Civil War prison site). For a moment nobody was sure why. After some brief confusion and closer inspection, it eventually became clear they had come from an organization called "Wreaths Across America."

And the purpose of the wreaths? They were to be placed at the graves at Andersonville's National Cemetery for the Christmas holidays as a way of honoring the sacrifice of the servicemen interred there. Thus began an annual practice, not just at Andersonville but at cemeteries across the country and around the world, of remembering America's war dead during the holiday season and rededicating her citizenry to the values that their dedication exemplified. This past Christmas season, on December 14, volunteers and supporters at more than 4,225 participating locations in all 50 states, at sea and abroad placed wreaths on our veterans' graves at local, national and military cemeteries as well as at Veterans' Memorials and historic sites. At Andersonville more than 20,000 veterans' graves were so honored last year. The wreaths donated for Wreaths Across America are produced at Worcester Wreath Co. of Harrington, Maine. Moving this cargo from Maine to Georgia is a complex process involving many hands. Each year the Bennett Family of Companies of McDonough, GA, and their charitable arm, the Taylor Family Foundation, provide the five tractor trailer trucks and truckers needed to transport the wreaths from Maine to Georgia. They also raise a sizable amount of the funds to purchase the wreaths in conjunction with their partner, Truist Bank. Unloading the trucks and handling the freight was accomplished with help from South Georgia Technical College which provided forklifts and operators. A Bennett executive serves as organizational lead for the project each year. Friends of Andersonville, a non-profit corporation that provides financial support to the Andersonville historic prison site, the National Cemetery, and the National POW Museum through endowment grants, and the AXPOW organization also made significant contributions to the project through the purchase of wreaths.

Finally, volunteers have to be recruited and trained for the respectful and somber process of placing the wreaths as well as the often-unnoted task of gathering and disposing of the wreaths later in January. Volunteers come together to attend a short ceremony where they are instructed on how to place each wreath, taking care to say aloud the veteran's name at each grave. In this most recent ceremony, more than 2,000 volunteers came to Andersonville to place wreaths. Three recent burials were notably honored: Corporal Luther Story, Korean War Medal of Honor Recipient and MIA for 73 years, Captain Jerry Riddle US Army and Specialist Desmond Campbell US Army. All told, last year 2.7 million veterans’ wreaths were placed at sites like Andersonville across the country and abroad. And more than two million volunteers participated. More than a third of those volunteers were children.

posted 2/8/24 Remembrances of Christmas from Another TimeThis “Christmas in Camp” compilation is on loan from the website of Imperial War Museums. IWM is a charity that seeks to serve as a global authority on conflict and its impact on people’s lives. It collects objects, stories, and audio and video segments all of which offer insights into people’s war experiences and preserves them for future generations.

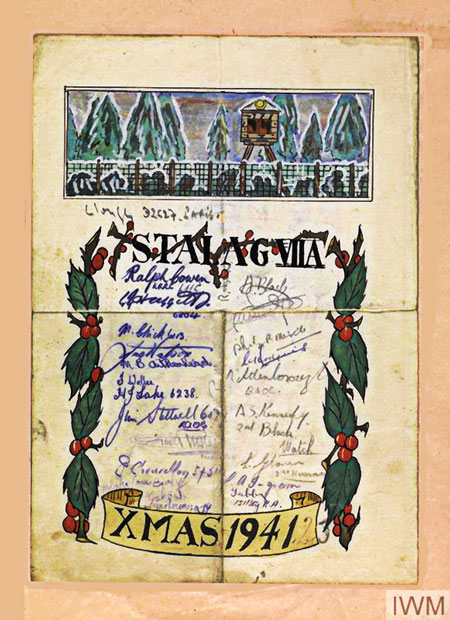

IWM manages five different museums, in London and Belfast, whose collections, in the organization’s own words, “explore the causes, course and consequences of war, from the First World War through to present-day conflicts.” For anyone with an abiding interest in the experience shared by those, both in and out of uniform, living contemporaneously with the disruption of war, the IWM website is well worth visiting. The charity holds over 20,000 individual collections of private papers and nearly 11 million photographs. It can be viewed at https://www.iwm.org.uk. Reprinted here with their kind permission. Christmas in Captivity'Joyeux Noel'Millions of prisoners were taken captive during the Second World War and their experiences varied according to many factors – from where they had been captured to their nationality, race and whether they were a civilian or serving in the military.

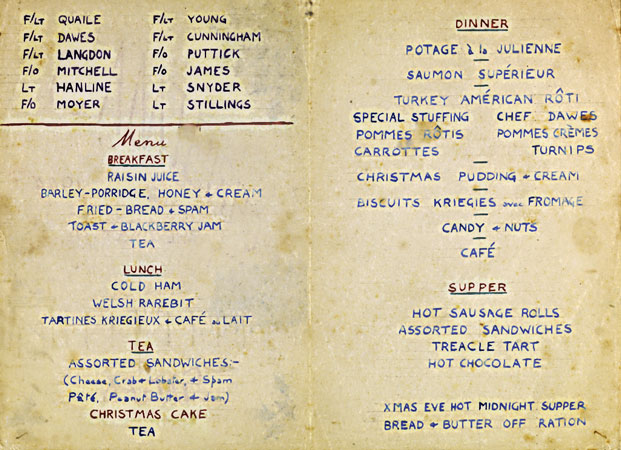

Though separated from friends and family and living in tightly controlled conditions, some prisoners were able to find ways to mark Christmas and New Year, using their creativity and comradeship to get them through. Explore these items from IWM’s collection to find out more about how POWs celebrated Christmas.  Three French POWs smile for the camera as they hold up their special Christmas offerings at Stalag Luft III, Sagan, December 25, 1942. © IWM (HU 20951) © IWM (HU 20951) Sharing a MealFlight Lieutenant Paul Cunningham’s Lancaster bomber was shot down over Scholven-Buer in Germany during a raid on June 21-22, 1944. He survived the crash but was captured and sent to Stalag Luft III. This Christmas menu from 1944 records the meal enjoyed by Cunningham and his fellow prisoners, largely based on the shared contents of Red Cross parcels.

Christmas menu from 1944 POW camp © IWM (Documents. 19672/B) Christmas in ColditzColditz Castle was a high-security prison and was the place the Germans sent their most difficult POWs—many of those held there had previously attempted escape from other camps. In this photo, prisoners pose for a photograph together in front of a Christmas tree.

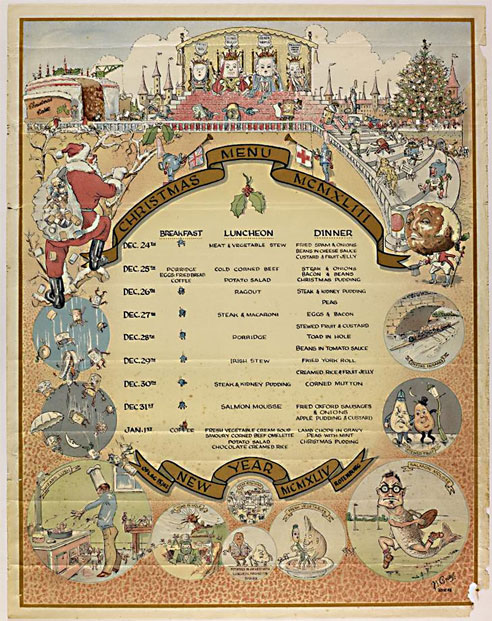

A group of British prisoners of war smile for the camera at Christmas. © IWM (HU 20276 'Breakfast, Luncheon and Dinner'Food is often at the center of Christmas celebrations. Prisoners held at Oflag IXA/Z in Germany created this beautifully illustrated poster advertising the Christmas and New Year menu at the camp—in one drawing, a pear in a policeman’s uniform arrests a "stewed fruit."

Illustrated poster made by POWs in Oflag IXA/Z, Rotenburg, advertising Christmas and New Year meals in the camp. (Click here to enlarge image.) ©IWM (Documents.7317/A ‘To Peglums’War separated loved ones, but people were sometimes able to find a way to communicate their feelings and seasonal wishes. James Buckley was held in Shamshuipo camp, Hong Kong. He sent this handmade card to his wife Margaret in 1942.

Handmade Christmas card sent by James Buckley to his wife, while a POW in Shamshuipo camp, Hong Kong. ©IWM (Documents.17928/A ‘From All German POWs of This Station’Despite being imprisoned on British soil, German soldiers were able to exercise their creativity in the camps and designed this Christmas card.

Handmade Christmas card from German prisoners of war still held in Farnborough, Hampshire in 1947.

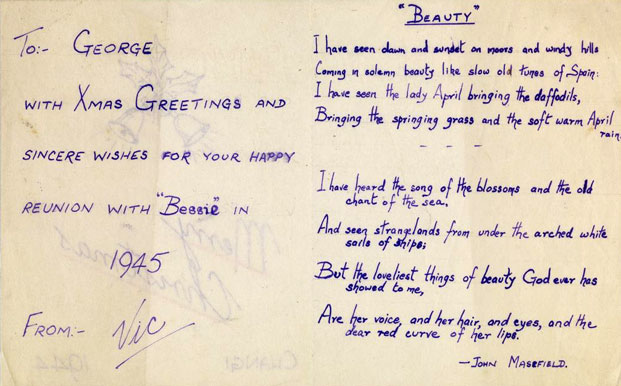

©IWM (Documents.8587/A Xmas GreetingsGeorge Charlton was a Staff Sergeant in the Royal Army Medical Corps who was imprisoned in Singapore from February 1942 to the end of the war, mainly in Changi camp until March 1945 when he was moved to the prisoner of war hospital at Kranji. He returned to the UK in October 1945. This handmade card was addressed to him at Christmas 1944.

Handmade Christmas card from Changi prisoner of war camp, Singapore, 1944.

©IWM (Documents.22679/A posted 12/13/23 Bombing Hitler's Gas Station, 1943Before Rockefeller discovered Pennsylvania, before Texas and Oklahoma, before Aramco, before the North Sea or Prudhoe Bay, before the Bakken Formation, there was Ploiești.

Romania, at the beginning of the 20th century, was one of the largest oil producers in the world. While its fields have now mostly matured, Romania drilled its first commercial oil well in 1857 and was the only country in the world that year to report significant crude oil production. The United States itself would not report any significant crude oil production until 1860. " They were flying so low — sometimes just 50 feet off the ground — that gunners on the bombers had to aim up at anti-aircraft guns positioned on the roofs of surrounding buildings."

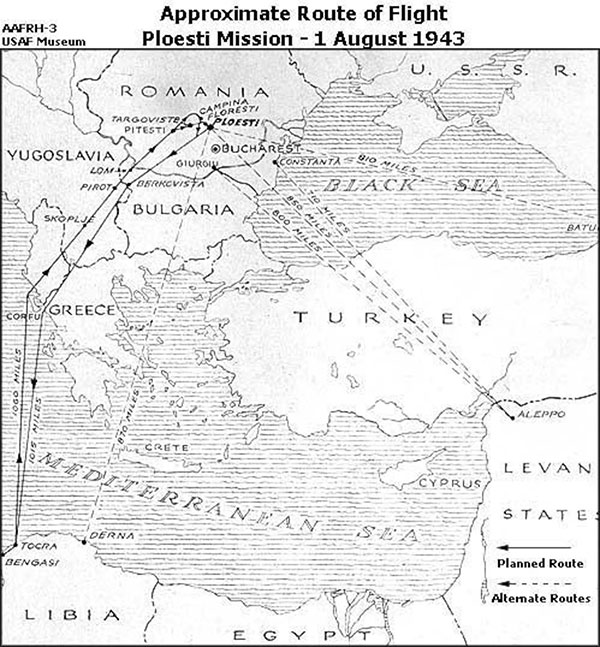

Three B-24 Liberator bombers, assigned to the 98th Bomb Group, fly a low-level bombing mission over the oil refineries around Ploiești, Romania, Aug. 1, 1943. (U.S. Air Force, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons) The refineries near Ploiești, an industrial center in eastern Romania near Bucharest and the Black Sea, provided one-third of the oil supply of the Axis forces in World War II. Which made it an obvious target for aerial attack. One such attack, Operation Tidal Wave, launched on Sunday, August 1, 1943, was perhaps the most spectacular American bombing mission of World War II or at least in its European theatre. It was a bold, low-level assault involving 178 B-24 Liberator heavy bombers. Five heavy bombardment groups took part in Operation Tidal Wave: two from Benghazi, North Africa (the 98th and 376th), and three sent from England to Libya (the 44th, 93rd and 389th). Combined these were all the B-24 groups then available in the European and Middle East theatre of operation. The Consolidated B-24D Liberator was the only American long-range heavy bomber that could reach Ploiești from the nearest Allied air bases in North Africa. A crew of up to 10 operated a B-24, which was over 66 feet long with a 110-foot wingspan. It had a top speed of just over 300 mph and a cruising speed of 200 mph. It could carry up to 8,000 pounds of bombs, and it was equipped with nine or more 50 caliber machine guns for self-defense. With a 5,000-lb bomb load the aircraft could range up to 2,850 miles. It weighed up to 56,000-lbs when loaded. For the Ploiești mission, about 2,100 miles from North Africa to the target and back, the B-24s were given increased fuel loads with fuel tanks placed inside their forward bomb bays, leaving the aft bomb bay to carry the bombs, either six 500 lb bombs or four 1,000-pounders, plus some incendiary clusters to drop. Some B-24s in the lead waves were given a pair of fixed 50 caliber machine guns fitted in the lower nose and fired by the pilot to help suppress enemy ground-based defenses. A few aircraft even carried twin 50 caliber waist guns.  B-24 over Ploiesti, Operation Tidal Wave (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons) Very early that Sunday morning, crews began taking off from Libya, flying in formation. Waves of B-24s followed each other, keeping radio silence and flying low to evade German radar. The planes were to fly across the Mediterranean and the Adriatic Sea, pass near the island of Corfu, cross over the Pindus Mountains in Albania, cross southern Yugoslavia, enter southwestern Romania, and turn east toward Ploiești where they were to locate pre-determined checkpoints, approach their targets from the north and strike all targets simultaneously. The attack was painstakingly designed and practiced repeatedly, but little went as planned. At the very start of the 1,000-mile run from Libya one aircraft crashed on take-off. Over the Mediterranean another began flying erratically and plunged into the sea for reasons still unknown. A plane descended from the formation to look for survivors, narrowly missing another aircraft in the process and then due to its additional fuel weight was unable to regain altitude to resume course to Ploiești. Ten other aircrews also proved unable to regain formation cohesion after the incident, hampered in their efforts by orders to maintain radio silence, and had to return to friendly air fields. The remaining aircraft next faced a steep ascent over the Pindus mountains, shrouded this day in a stormy cloud cover. The clouds broke the formation into two groups. Although all five groups made the 11,000 ft climb, the first two groups (the 376th and 93d), flying higher and using higher engine power settings, pulled ahead of the trailing formations (the 98th, 44th and 389th), creating speed and time variations that would disrupt the synchronization of the group attacks. After the mountains, the gap had grown to 20 minutes. Precise timing and distance were critical for the bombers to all reach their targets at the right time and in the correct intervals.  Public domain, USAF Museum via Wikimedia Commons

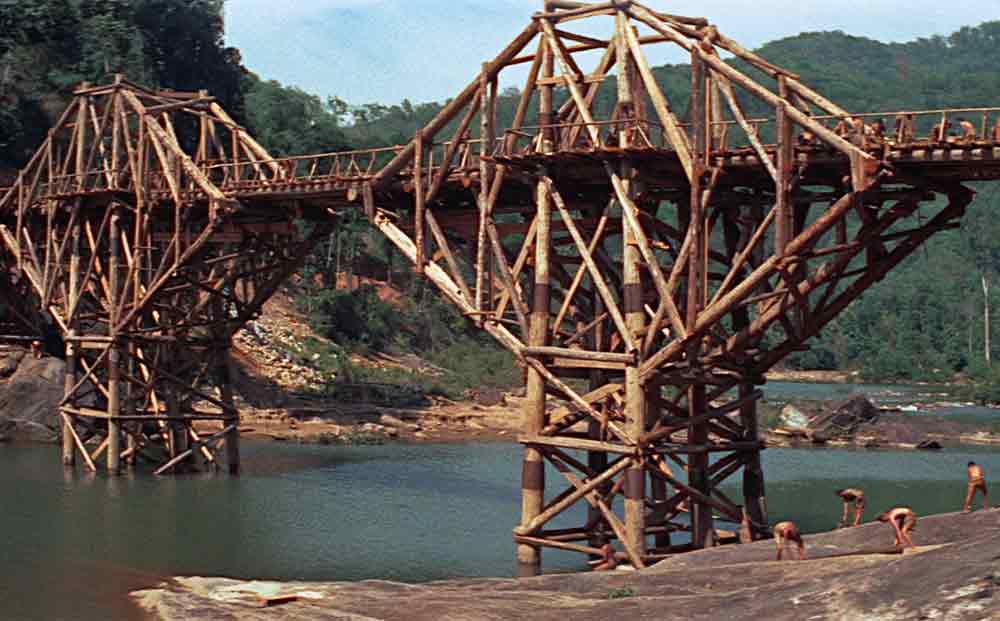

Then navigation issues led entire squadrons off course.A disastrous premature right turn just short of the final initial checkpoint set the two leading bomber groups on a course to Bucharest instead of Ploiesti. The correction, when they finally made it, forced the bombers to approach their targets from the south, where the Nazis had concentrated their anti-aircraft batteries, rather than from the north as planned. Arriving over a heavily-defended target area, disorganized and without the planned element of surprise, The Allied airmen encountered heavy resistance. The Germans knew more about the raid and were far better prepared for it than the Allies anticipated. The ensuing attack proved dramatic, chaotic and costly. Disguised defenses, such as anti-aircraft guns hidden among train tracks, oil tanks, and surrounding fields, greeted the bombers as they approached their targets. Billowing clouds of black smoke limited visibility and interfered with navigation as the B-24s descended to drop their bombs. They were flying so low — sometimes just 50 feet off the ground — that gunners on the bombers had to aim up at anti-aircraft guns positioned on the roofs of surrounding buildings. Explosions from the ordinance dropped by the first groups of bombers made visibility even more difficult for the later groups, which were essentially following, or even flying into, their predecessors' paths. Compounding the confusion, some of those planes had abandoned their original assignments in favor of bombing more accessable "targets of opportunity." The three trailing groups, discovering assigned original targets had already been hit, also had to pick targets out by sight and try to bomb whatever refineries they could see. Facing a fiery landscape black with thick smoke, withering ground fire coming at them from both above and below, and 60-foot flames shooting up higher than their aircraft were flying, some bombardiers jettisoned their payload before even finding a target. Pilots began looking for someplace to set down their bullet-riddled planes before being shot down or set ablaze by the inferno raging below them. One of the downed planes crashed into a female prison in Ploiești, killing a reported 100 civilians and injuring 200 others. 88 B-24s returned to Libya; 55 had battle damage. German air defenses accounted for 44 of the losses. Additional B-24s ditched in the Mediterranean on the return trip or were interned after landing in neutral Turkey. One B-24 with 365 bullet holes landed in Libya 14 hours after departing. A total of 23 others landed at Allied bases in Cyprus, Malta and Sicily. The Americans sustained 310 air crewmen killed or missing, 108 captured by the Axis, 78 interned in Turkey, and four taken in by Tito's partisans in Yugoslavia. Of 178 bombers and 1,726 men on the mission, 54 aircraft and nearly 500 men failed to return. Although the raid significantly damaged Ploiesti's oil facilities, the enemy quickly restored production. Tidal Wave succeeded in destroying two of nine refineries and damaging three others. Despite the extreme heroism of the airmen (five Medals of Honor awarded the most for any single air action in history—three posthumously) and their determination to press the mission home, the results of Operation Tidal Wave were less than expected. The targeted refineries produced some 8,595,000 tons of oil annually. The attack temporarily eliminated about 3,925,000 tons. Three refineries lost 100 percent of production but the Germans restored production surprisingly quickly. The largest and most important refinery target, Astro Romana, was back to full production within a few months; Concordia Vega was operating at 100 percent by mid-September. Even so, notwithstanding its high cost in materiel and human lives, Tidal Wave strategically proved in some respects a moderate success. Falling far short of the original goals, it did cut Germany's oil distillation capacity at a time when her war machine needed it most to confront the Red Army’s drive toward the Fatherland. The Reich ran painfully short of fuel for combat, transportation and training. Ploiești was not attacked again until April 1944. Nearly a year after Tidal Wave, heavy bombers again appeared in the skies over the oil refineries. This time they flew at over 28,000 feet. (The U.S. Army Air Forces never again attempted a low-level mission against German air defenses.) They again took heavy losses but dropped sufficient ordinance on their targets that, while Ploiești never stopped producing fuel, the the German army found itself living off rapidly diminishing stockpiles as it used up gasoline and aviation fuel to fend off the advancing Allied armies. As World War II began, Romania had been a neutral country Amidst rising Fascist political sentiment, a coup in September 1940 deposed the country's king and turned the government into a dictatorship under Marshal Ion Antonescu, a far-right leaning, and highly anti-Semitic, career military officer in Romania's army. The new regime officially joined the Axis powers in November 1940 and brought with it what was the third-largest Axis army in Europe. But as the war wore on, besieged by relentless Allied aerial attacks and heavy troop losses on the Eastern Front, the nation's popular support for the war faltered. In a late summer offensive in 1944 the Soviet Red Army overtook the Ploiești oilfields— days before King Michael, son of the previously deposed King Carol II, led a coup d'état that toppled the Antonescu regime and put Romania on the side of the Allies for the remainder of the war.  National Museum of the Oil Industry, Ploiesti Romania National Museum of the Oil Industry, Ploiesti RomaniaRomania today ranks 44th globally in proven oil reserves. Ploieşti, with its refineries, storage tanks, oil-field equipment works and distillery, remains the country’s primary petroleum center. The Encyclopedia Britannica notes it is also a cultural center, with six museums (including the National Oil Museum, which traces the development of the Romanian petroleum industry). posted 8/22/23 The Golden Anniversary of 591 Personal VictoriesOn January 27, 1973, Henry Kissinger (then President Richard Nixon’s National Security Advisor) reached a ceasefire agreement with North Vietnam providing for the withdrawal of American military forces from South Vietnam and the release of nearly 600 American prisoners of war held by North Vietnam and its allies. That was fifty years ago this year.

U.S. Marines in Vietnam, the war that would not end, 1971-1973 (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

The returnees maintained their composure until it was clear they were again safe under American control. No one was silent as the Air Force C0141 Starlifter left the runwaty at Hanoi. The photographer, TSgt Robert N. Denham, USAF, observed, "You could hear the shouts all over the aircraft" on this 28 March 1973 flight. Department of Defense Photo (USMC).

Under the terms of Operation Homecoming, as it was dubbed, POWs held by the Viet Cong were flown by helicopter to Saigon, POWs held by the People's Army of Vietnam were released in Hanoi and three POWs held in China were freed in Hong Kong. From there they were flown to Clark Air Base in the Philippines for processing, debriefing and physical examinations. They were then relocated to military hospitals. Of the POWs repatriated to the United States a total of 325 served in the United States Air Force, a majority of them bomber pilots shot down over North Vietnam or VC controlled territory. The remaining 266 consisted of 138 United States Naval personnel, 77 soldiers serving in the United States Army, 26 United States Marines and 25 civilian employees of American government agencies. A majority of the POWs were held at camps in North Vietnam, while some were held in at various locations throughout Southeast Asia. The prisoners returned included future politicians Senator John McCain of Arizona, vice-presidential candidate James Stockdale, and Representative Sam Johnson of Texas. (For a young, newly married wife's first-person account of her own journey through the dark period spanning her husband's capture and release, see "Operation Homecoming from Beginning to End… A Young Wife’s Personal Perspective" below.)

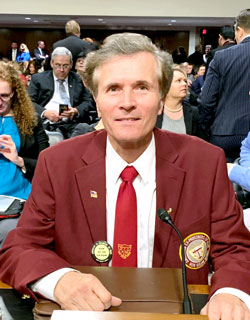

Operation Homecoming provided the country with moment of drama and celebration and ignited a torrent of patriotism that had not been seen at any point during the Vietnam War. President Nixon celebrated the return of the Vietnam POWs hosting an estimated 1,600 guests at a banquet held in a tent on the White House South Lawn. The tent was longer and wider than The White House itself, with 126 round tables set up for the guests. That banquet was—and remains—the largest in White House history. The menu included All-American fare: sirloin steak, fingerling potatoes and strawberry mousse The 591 former POWs, in full dress uniform, were entertained by comedian Bob Hope, who served as master of ceremonies, and mingled with senior military and government officials to celebrate their return. Other celebrities in attendance included John Wayne, Jimmy Stewart, Phyllis Diller, and Sammy Davis Jr. Irving Berlin along with the President and his wife Pat, joined by Sammy Davis Jr. and Bob Hope, concluded the evening by leading the guests in the singing of his American standard, “God Bless America.” In May of this year, in recognition of the Golden Anniversary of Operation Homecoming, numerous military installations conducted commemorative events celebrating once more the return of the American POWs 50 years ago. On the National Mall in Washington, the U.S. Vietnam War Commemorationan, authorized by Congress, established under the Secretary of Defense and launched by President Obama in 2012, sponsored a public exposition meant to honor those who served in the military during the war. Tents with different war-related exhibits were scattered across the Mall. Vietnam-era helicopters were on display. About 200 posters were positioned along the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool, each with the face and name of troops still unaccounted for. The Nixon Foundation was the Official Site of the 50th Anniversary Commemoration of Operation Homecoming. On May 23-25, nearly 200 POWs and their families gathered at the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum in Yorba Linda, CA, for a three-day reunion. Events included a community parade, recognition and honors from the U.S. Military, the official opening of a new exhibit, Captured: Shot Down in Vietnam, and an opportunity to hear reflections from the POWs themselves and their stories of survival and endurance in the face of physical and emotional torture, and of the bonds of brotherhood and faith that helped them persevere. On May 24, Nearly 150 former American Prisoners of War from the Vietnam War gathered in the East Room of the Nixon Library for a re-creation of the White House homecoming celebration dinner fifty years before to the day. The reenactment featured the menu selections and table centerpieces evocative of the style the original banquet in 1973. Several YouTube video clips have been posted in connection with the Golden Anniversary of Operation Homecoming, including the following.

Vietnam POW Homecoming Gala at the Nixon Library (May 24, 2023) Vietnam POW Welcome Celebration at the Nixon Library (May 23, 2023) Panel Discussion: Resilience, Fortitude and Faith: Vietnam War POWs Reflect 50 Years Later (May 25, 2023) Since 1973, more than 1,000 missing service members have had their remains returned to the United States for burial with full military honors. There are 1,581 Americans from the Vietnam War still missing in action.

Operation Homecoming, Beginning

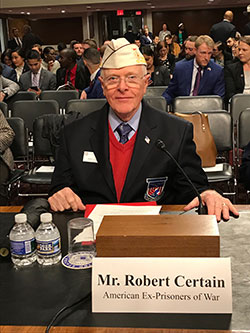

to End … a young wife’s personal perspective A memoir by Robbie Wade Certain

The circumstances of my life had prepared me for what I was letting myself in for, at least somewhat. But I had never dated a military officer before July 21, 1971. I was 22 years old. I had grown up in Blytheville, Arkansas, which had a B52G Air Force base. I was aware of this plane and understood its purpose as far back as elementary school. I actually had witnessed the arrival of the first plane at the base. I knew about the “red phone.” I was acquainted with Air Force officers and their children. I felt comfortable with the military and its lifestyle. I knew that B52s could carry nuclear weapons. I also knew they were very good airplanes with excellent safety records. But until 1971 all of that existed mainly on the periphery of my consciousness. I had come home to Blytheville after graduate school to teach, but it was love at first sight. Robert was a first lieutenant and a navigator bombardier. He had already been flying missions for four months (without incident). Then after 10 nights of dating, my future husband left me to go to Thailand. He came home at Thanksgiving, and we were engaged by New Year’s Eve. A perfect time to wed would be June. Plans were made for an elaborate event, a large wedding because Blytheville was, after all, my hometown. Life was progressing. School was winding down for the summer. And I was ready to marry my capable young officer. Ah, man plans and the gods laugh. B52s and their crews stood alert for seven days a month. The planes had to be ready to defend the nation at a moment’s notice. Wives, girlfriends, and families had visiting privileges at the Blytheville AFB when their men were on active duty, and one Sunday evening in May I went out to visit. It didn’t go as either of us had expected. Robert had been informed earlier in the day that all planes would be leaving for Guam by the end of the following week. So, I could marry Robert by the week’s end or wait for his return in six months. What a week. For all of us. I made an important decision and married him five days later. I had no idea what was ahead. Specifically, we were wed on May 25, 1972. As luck would have it, we wound up with six whole weeks of married life together before he left for Guam. We communicated after that daily by letter. We had two phone calls in six months. Phone calls to Guam were six dollars a minute at the time! I kept busy teaching two sessions of kindergarten daily and teaching community college two nights a week. Robert was due home the first week in December, but his orders were cancelled. The new date of return was December 18. I was so excited. I decorated the house with a tree and a manger scene he had made in the base hobby shop. He liked to say he made it “between bombing runs.” A Colonel had brought it to me in mid-December. Life was looking up. We were going to resume our young marriage. But when December 18 came, my world changed very unexpectedly. No matter how steady and solid you think you are, no one is prepared for the arrival of a notification of wartime status of a loved one. It was Christmas break, and I had gone home to have lunch with my parents. I had planned to pick Robert up in the morning hours of December 19. While I was eating lunch, my mother answered the phone and received news that military officers had been by my father's furniture store looking for him. Our salesman asked that my father stay home and wait until the officers arrived. At that point, I was sure something was wrong. I lost all interest in eating and began pacing the floor, pondering what could be going on. My parents were saying don't worry, but my stomach knew better. Some time earlier, a pilot’s wife had told me to never worry until the white-top cars show up. Well, two white- top cars were sitting outside our front door with at least six officers inside. This was my worst nightmare coming true. My mother and father had their arms around me as the notifying officer read a letter explaining that Robert had been shot down over Hanoi and was classified as Missing in Action. I didn’t know that B52s were flying over North Vietnam. Robert had not warned me that he would not be home on the 18th although he was suspicious with all the activities going on in Guam. Information was hush, hush, and men were not being informed of anything ahead of time. The whole world exploded, for me and other family members. The visiting officers expressed their sympathies. At that time, my father and mother were serving as liaison officers to the base, so there was a lot of respect and concern shown to us. I was going to go lie down and rest a little when another phone call came in, with better news. Robert's Social Security number was being released by Radio Hanoi. The next morning Robert’s picture along with those of five other officers was published around the world in every major newspaper. We were all learning about the United States attack on Hanoi. President Nixon hoped that bombing Hanoi would bring North Vietnam back to the bargaining table to end the war and bring all the POWs home. This was the beginning of Linebacker II. The bombing runs lasted for 11 days. My husband just happened to be on the first airplane to go down over Hanoi and was the first one captured. That was the start, for me, of Operation Homecoming. I had no idea when my husband would be home. I had only just been notified by the military, and they were supporting me with all the information they could. My job was to go on with my life, live it as a schoolteacher and a wife with a husband in the “Hanoi Hilton.” What could be more normal? But all my sights were set all along on the day my Robert would come back home to me. I have always been happy with my decision to marry before Robert went to Guam. I am sure I would not have gotten the information I did get as quickly, as a fiancée. I realized later in life that, in essence, I’d become a war bride, just like the young women of World War II. The good news? the bombing did the trick. Everybody came back to the table and started talking. The bad news? Over 30 men died in Linebacker II. A peace treaty was signed in January, and life was looking hopeful. We didn't know exactly how Operation Homecoming would work out, but we were getting informed each time a group of men were being flown home. As each release came, I would be notified that Robert was or was not on the airplane. But by the second release I'd figured out that the last ones in were going to be the last ones out. It was fair, but each time I got the same discouraging message my stomach would tie itself up in knots.

(caption)

B'VILLE POWS FREED--Blytheville Air Force POWs recently returned to the United States. From left they are: Capt. Richard C. Simpson, Capt. Robert G. Certain, Maj. Richard E. Johnson and TSgt James L. Lollar. The former B-52 crew members are currently under the authority of the Air Force and have been at Scott AFB, Ill. and Maxwell AFB, Ala. undergoing physical examinations and debriefings. And indeed, Robert was on the last plane to leave Hanoi. He called me when he reached the Philippines. Oh, that was a happy day for me. It would be only a few more days before I saw him again. He would be taken first to Scott Air Force Base in Belleville, IL, the closest major military hospital to Blytheville AFB. I don't remember much about the drive to Belleville, but I know that I had with me 30 pieces of paper orders in case I needed any one of them while on the base. At Scott I was greeted by an escort officer and his wife, Maj. and Mrs. DeCamillo. They were delightful and treated me well. The first thing they did was take me to the hospital for medicine. When I arrived at Scott I had a cold, a cough and a runny nose. Robert was to arrive the next day. President Nixon had arranged corsages for all the wives to wear upon meeting their husbands. My teaching assistant had also arranged for a red carnation corsage for me, a gift from my kindergarten students, who had brought in pennies, nickels and dimes to pay for it. I had to wear the carnations, which meant so much to me. The children knew all about the shoot-down and my husband’s incarceration. He was a hero to them. I learned a life lesson that day at Scott that has stayed with me through the years: stress can make you sick. Robert got off the airplane, hugged me and the cold was gone! Robert’s parents, my sister and her husband, and some very good friends from Blytheville AFB had come with us. Even Robert’s second grade teacher, who lived in the area, was there to welcome him home. The event was joyous, surreal and heavy. As happy and elated as we were, I was very mindful at that moment of the sacrifices other men and families had made. Some children would never know their fathers. Robert and I were newlyweds, and I felt how blessed we had been, but my joy was measured with emotions for other families. Robert and I attended the lavish White House dinner President Nixon hosted for the repatriated POWs on May 24, 1973. We considered it our first wedding anniversary party. Memories of that evening include the military bands playing as we got off the bus, the red carpet, moving to the bar area and meeting John Wayne, being escorted to the tables, flowing wine and champagne, our glasses were never empty, Bob Hope and Sammy Davis Jr., meeting Joey Heatherton in the ladies’ room and the crowning glory of the evening: Irving Berlin leading us in singing “God Bless America.” A fabulous evening in all details (the cherry tomatoes in the salad had been peeled). But in the midst of it all, my thoughts turned more than once to the three of Robert’s crew members who did not come home. One was MIA, one was reported killed and another’s body was shown to Robert in North Vietnam. We were still only 24 and 25 years old at the time of that dinner, after all that had gone before. Our marriage of 50 years has survived through the myriad bumps and challenges of life. We live at Blue Skies of Texas in San Antonio. (Formerly known as Air Force Village.) We have one son and one daughter and son-in-law with two teenage children, all living in Little Rock. We are content. We were at the Nixon Presidential Library this year for the 50th anniversary celebration of Operation Homecoming. A smaller scale with fewer celebrities, but a very familiar ambiance. Same table arrangements. Same menu. Same elegant assemblage. And the same waves of conflicting emotion. Gratitude for our great good fortune, sorrow for the loss and pain suffered by so many who sacrificed so much. I’m sure it will always be that way whenever I think back on it all, and I think back on it often. posted 7/13/23 Andersonville Marks National POW/MIA Recognition DayNational POW/MIA Recognition Day was established by Congress to honor those armed service members held captive, who returned or who remain missing, while fighting in the nation's foreign wars. In 1979 a Congressional proclamation signed by President Carter declared the third Friday in September as National POW/MIA Recognition Day. Each subsequent president has issued his own annual proclamation commemorating National POW/MIA Recognition Day.

This year to honor that tradition, Andersonville National Historic Site and the National Prisoner of War Museum conducted on September 16 a ceremonial wreath laying in remembrance of the sacrifice of those Americans who gave up their freedom on their nation's behalf.

Gia Wagner, Superintendent of the Historic Site, presided at the ceremony and explained the occasion would be marked, in cooperation with representatives of two of Site's most important support groups, American Ex-Prisoners of War and Friends of Andersonville, with the placement of three wreaths. Col. Wayne Waddell, US Air Force Retired and former POW during the Vietnam War, presented the Friends of Andersonville wreath. Sally Morgan, who was a child civilian internee during World War II at the Santo Tomas internment camp in the Philippines, presented the American Ex-Prisoners of War wreath. Col. David Eberly, US Air Force Retired, was the Senior Ranking Officer of all POWs captured in the 1991 Gulf War. He presented a wreath commemorating all POWs and those still officially missing in action. Superintendent Wagner addressed the crowd of attendees: "Today, at the National Prisoner of War Museum, which was designated by Congress as a memorial to all POWs throughout American History, "Such a large number is hard to fathom, but today especially, we remember them as individuals with families—whose stories and sacrifices deserve to be remembered and shared with future generations of Americans. I invite you to take a moment to reflect on those individuals." The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, an arm of the Department of Defense, estimates there are more than 81,000 Americans still missing from past conflicts ranging from WWII to the Gulf War. In fiscal year 2022, the DPAA has completed nearly 100 missions in 37 countries searching for American personnel and has accounted for more than 140 missing American military members. Andersonville National Historic Site, located near Americus, GA, has three features: the National Prisoner of War Museum, the site of the Andersonville prison, and the Andersonville National Cemetery. The National Prisoner of War Museum commemorates the sacrifices of all American prisoners of war. posted 11/13/22 Where Have All the Flowers Gone?Congress designated the country's first federal holidays in 1870: granting paid time off to federal workers in the District of Columbia for New Year’s Day, Independence Day, Thanksgiving Day and Christmas Day. In 1888, it created Decoration Day, now known as Memorial Day.

The practice of honoring soldiers fallen in battle dates back thousands of years. Both the Greeks and Romans held annual days of remembrance each year for fallen soldiers, decorating their graves with flowers and holding public festivals and feasts in their honor. In Athens, public funerals for war dead were held after each battle. One of the first such public tributes took place in 431 B.C., with the Athenian general and statesman Pericles offering a funeral oration praising the sacrifice and valor of those killed in the Peloponnesian War, in a speech often compared to Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address.

Arlington National Cemetery, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In the years following the end of the Civil War increasing numbers of American communities began ritually tending to the remains and graves of an unprecedented number of fallen soldiers. (All of the previous wars and conflicts fought by the United States combined barely add up to the body count the country suffered in the Civil War.) A few local springtime tributes to Civil War dead began even before hostilities had ceased. In Columbus, MS., April 25, 1866, it has been recorded that a group of women visited a cemetery to decorate the graves of Confederate soldiers who had fallen in battle at Shiloh. Nearby were the graves of Union soldiers, neglected because they were the enemy. Disturbed at the sight of the bare graves, the women placed flowers on their mounds as well. Three weeks after the Confederate surrender, on May 1, 1865, more than 1,000 people recently freed from enslavement, accompanied by regiments of the U.S. Colored Troops (including the Massachusetts 54th Infantry) and a group of white Charlestonians, gathered at a former war prisoner detention camp in Charleston, SC to consecrate a burial site for Union dead. Near the war's end, thousands of Union soldiers held as prisoners of war had been herded into a series of hastily assembled camps on the site of a former racetrack in Charleston. Conditions at one camp were such that more than 250 prisoners died from disease or exposure and had been buried in a mass grave behind the track’s grandstand. The gatherers sang hymns, gave readings and distributed flowers around the cemetery, which they dedicated to the "Martyrs of the Race Course." Cities in the North and South who claim to be the birthplace of Memorial Day.

For almost as long as there’s been an observance, there’s been a rivalry over who celebrated it first. All told, more than 20 towns claim to be the holiday’s birthplace. One has even received federal recognition. In 1966, 100 years after the town of Waterloo, New York, first shuttered its businesses and took to the streets for the first of many continuous, community-wide celebrations, President Johnson signed Congressional legislation declaring that tiny upstate village the “official” birthplace of Memorial Day

Some other contenders include the following: Warrenton, VA on June 3, 1861. The first Civil War soldier's grave ever to be decorated, according to a Richmond Times-Dispatch article in 1906, for the first soldier killed in action during the Civil War. (John Quincy Marr at the Battle of Fairfax Courthouse. Savannah, GA in July 1862. Women decorated the graves at Laurel Grove Cemetery of comrades who died at Battle of Manassas (First Battle of Bull Run). Jackson, MS in April 26, 1865. One Sue Landon Vaughan is said to have decorated the graves of Confederate and Union soldiers. However, the earliest recorded reference to this event did not appear until many years after. Regardless, mention of the observance is inscribed on the southeast panel of the Confederate Monument in Jackson, erected in 1891. Gettysburg, PA in 1863. The National cemetery dedication there included a ceremony of commemoration at the graves of dead soldiers. Some have therefore claimed that President Abraham Lincoln was the founder of Memorial Day. Carbondale, IL in 1866. Returning veterans, inspired by the sight of a young woman with infants at a small, unmarked grave in a church yard cemetery placing flowers and kneeling in prayer next to it, organized a memorial service to honor those who had died in the Civil War. Colonel E. J. Ingersoll, and General John A. Logan of the Union Army, led a procession to the town's Woodlawn Cemetery, where a number of Civil War soldiers had been interred. Columbus, GA in March 1866. Another Southern city named Columbus is credited by the United States National Park Service and numerous scholars for beginning Memorial Day observances in the South. The Ladies Memorial Association of Columbus members in a letter to newspapers in March 1866 asked for assistance in establishing an annual holiday to decorate the graves of soldiers throughout the South. It was reprinted by papers in several Southern states, and the plans were noted in newspapers in the North as well. On the chosen date, April 26, observances were held in Atlanta, Augusta, Macon, Columbus and elsewhere in Georgia as well as Montgomery, Alabama; Memphis, Tennessee; Louisville, Kentucky; New Orleans, Louisiana; and Jackson, Mississippi. Boalsburg, PA in October 1864. Only 100 miles away from Gettysburg, this small abolitionist community suffered multiple causalities throughout the Civil War. According to local historians, three local women, Emma Hunter, Elizabeth Meyer, and Sophie Keller, shared a bouquet of flowers on an autumnal Sunday and decorated the graves of their family members and friends. There are doubters of the veracity of Boalsburg's claim and its timing, but if true, the federal government might need to wrestle with the logistics of having to repurpose Memorial Day into a fall holiday. On May 5, 1868, Maj. Gen. John A. Logan, by then head of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), an organization of Union veterans, called for a nationwide day of remembrance later that month, declaring it "Decoration Day," a time for the nation to decorate the graves of the war dead with flowers. Logan is generally considered the leading figure behind the effort to recognize Memorial Day as an official holiday. (He would in time serve as a U.S. Congressman and Senator from Illinois and in 1884 was a candidate for the vice presidency.)

Headquarters Grand Army of the Republic,

Washington, D.C., May 5, 1868. GENERAL ORDERS No. 11 The 30th day of May, 1868 is designated for the purpose of strewing with flowers or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion, and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village, and hamlet churchyard in the land. In this observance no form or ceremony is prescribed, but posts and comrades will in their own way arrange such fitting services and testimonials of respect as circumstances may permit That first year, more than 27 states held some sort of ceremony, with more than 5,000 people attending a ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery. General James Garfield made a speech and 5,000 participants decorated the graves of the 20,000 Civil War soldiers buried there. The country embraced the notion of Decoration Day. Many Northern states held similar commemorative events and reprised the tradition in subsequent years; by 1890 each one had made Decoration Day an official state holiday. Southern states, on the other hand, continued to honor the dead on separate days until after World War I. It was yet not an official holiday, but many local municipalities and states adopted resolutions over the following years that recognized Decoration Day as an official holiday in their areas. By 1890, every former state of the Union had adopted it as an official holiday.

The first Memorial Day observation at Arlington National Cemetery was held on the portico of Arlington House. Photographers used cameras with two lenses to capture twin images and these were then printed side-by-side on card stock in a format known as “stereoview cards.” When viewed through a Holmes stereoscope (invented by Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., father of the US Supreme Court justice), these cards yielded three dimensional images similar to 3D movies and images today. Arlington House, a stately mansion with a commanding view of the nation’s capital just across the Potomac River, was the former home of Confederate General Robert E. Lee and his family, confiscated by the federal government after the war. (Library of Congress)

For more than 50 years, the holiday was used to commemorate those killed just in the Civil War. With America’s entry into World War I the tradition was expanded to include those lost in all wars. Memorial Day was not officially recognized nationwide until the 1970s, with America then embroiled in the Vietnam War. In 1968, the U.S. government passed the Uniform Monday Holiday Act, which put major holidays on specific Mondays to give federal employees three-day weekends. Memorial Day was one of those holidays, along with Washington's Birthday, Labor Day and Columbus Day. The act also codified the name "Memorial Day" into law. The act officially went into effect in 1971

Preparing to decorate graves, May 1899 (Library of Congress)

In the years following the Civil War, Lincoln's aspiration that we should be a nation characterized by malice toward none and charity for all visibly manifested itself in the magnanimity of Americans on both sides of the conflict. After having fought so fiercely over the country both loved, each side collectively extended an olive branch to mourn and to honor the estimated 620,000 men who gave "the last full measure of devotion" in that bitter conflict. (We should do so well today.) posted 5/28/22 A Note to Our Readers

After 80 years of serving veterans, and more than half a century of helping veterans and their dependents obtain the finest quality care and assistance in filing claims, the American Ex-Prisoners of War has made the difficult decision to cease certifying service officers as well as accepting new claims. The Veterans Administration OGC has agreed to put a notice on their website, and we are doing the same on ours with this notice. To our loyal NSOs, please accept our heartfelt gratitude for your years as accredited service officers with AXPOW. Many thousands of veterans and their families are also grateful for your help. Current, active claims will continue under our certification for the next couple of years as we wind down operations. Please let your claimants know that a new POA will need to be signed allowing you to continue representing them under another VSO’s accrediting authority.

Again, thank you for your service to the American Ex-Prisoners of War and all veterans. Cheryl Cerbone posted 1/24/22 Recollections of Christmases PastWhat are your fondest Christmas memories, made so many years ago? Mental images you carry with you even today, burned into your very identity. Likely, some from as far back as the impressionable years of early childhood. Warm and happy recollections, of moments that even today make the holiday season one of the more joyful events in your life each year.

Many of our AXPOW members carry different, and darker, Christmas memories with them from the dispiriting, and sometimes seemingly endless, times thrust upon them as incarcerated prisoners of war in foreign lands far from their homes.

National Archives at College Park

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Some members felt compelled to recall those memories in the first-hand biographies they wrote out for our POW Biography database. Still fresh enough in their minds so long after the fact. Memories they could not let go of, and which no doubt shaped them just as did those happy Christmas recollections absorbed in innocent years. (Although most were not that removed from those innocent years when they went off to serve their country and fight for its freedoms. The burdens of war are borne disproportionately by the young.) These stories are ones of deprivation, fear and uncertainty, dislocation and discouragement, but also of abiding hope and a very American will to endure, outlast and overcome their present circumstances. This year as you pause to pray, give thanks or just enjoy this happy seasonal lull in our daily routines, take a moment to recall and offer a prayer of thanks for the men and women, some still living in our midst, many now in our memories, for the courage and commitment they showed in the field and in prison camps to secure that way of life we remain free to live today. Herewith, camp memories at Christmas time by POWs who fought in the European theater during World War II, as they themselves recorded them, drawn from the annals of our members' biographies. Powers, Harry, Army Air Force, 390 Bomb. Group, 571 BS, captured Sept. 14,1943, Dulag Luft, Germany, Stalag 17B, Krems, Austria, Braneau, Austria, Interned 247 days, Age 20.

"I think the uncertainty of what the next day would bring, along with the starvation, cold temperatures, fleas, and the second Christmas of still being there and constant threats of being shot was the worst. We dug a few tunnels but somehow the guards always found out about them, so there were no escapes. We were there for twenty months until our eighteen-day march west to Braneau, Austria. We were liberated on April 5th by Gen. George Patton. My weight was down to about 114 pounds—we were always hungry." Liner, Ernest G., Army Air Corps, captured Aug. 22,1944 in Germany, Stalag Luft 4, Interned 247 days, Age 23.

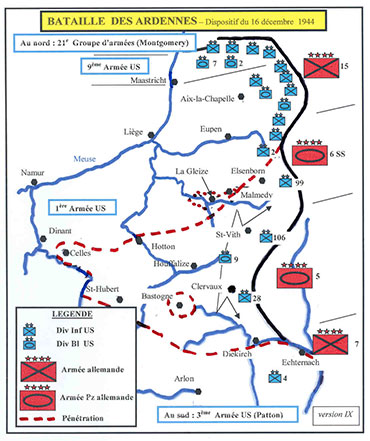

"Twenty-two men in our room and all of the rooms were alike. Each room had a little coal stove, and we got three bricks of coal a day. Bunks were built around the room, each three high and two wide. Peterson and I slept together, as most of us had one partner with whom we divided food, shared clothes and ate together. Christmas time was coming, which made it harder for everyone. One guy in our room suggested that we start saving our food for the holidays. Then the idea came to make a cake for Christmas day. Each one of us would give something from our parcels such as powdered milk, chocolate, sugar, or salt. When the day came we had lots of food and a beautiful, big cake. Some men in another room had fermented sugar, raisins and other things to make alcohol, and we traded some of our cake for enough alcohol for all of us to have a couple of swigs. The alcohol was very potent, especially on our empty stomachs with that rich cake. Years later there an article about our cake appeared in The American Legion Magazine, December 1957. Some of the men in our room had received musical instruments from home or they were able to get the guards to get instruments for them. These musicians would get together and play. At Christmas the Germans allowed us to use a large hall and the men with instruments gave a wild party. You should have seen the crazy dancing that was done. Until the last song, 'White Christmas,' was played. After that each one of us went back to our room with tears rolling down our cheeks. We were getting some war news from a small radio, the size of a pack of cigarettes that had been smuggled in a piece at the time and kept secret all the time we were there. We could receive the BBC once a day on a certain wavelength. One person listened, and told some other men who, in turn, told other men in each of the other barracks to spread the news of the day." Clark, John R, Army, captured Dec. 21. 1944 at Battle of the Bulge, Stalag 8A And 4B, Interned 113 days, Age 19.

"Clark's ordeal began with a three-day march from St. Vith, Belgium to Prum, Germany. They were given no food during the march. Finally, they reached a railhead, where they were loaded onto box cars, headed for POW camps. They had only been on the train for a part of the day before it had to stop because the American Air Force had bombed the trestles. The boxcars were moved to a siding. Later, an American P-51 shot up the train killing six and wounding 47. The soldier sitting on Clark's left and the one sitting on his right were both killed. Clark said the prisoners then broke the doors down and laid in the snow linking their bodies together to form the words 'USPW.' The plane came back and rolled its wing (in salute). This was the day before Christmas. We spent the night back in the rail cars. On Christmas, we got a half-loaf of bread and a spoon of jam. This was for two days. After marching for three days they were put on another train. Again, they were bombed by their own planes but finally reached the prison camps. During in processing, a German officer took all of Clark's possessions, handing him a receipt for the few dollars and francs he carried. Clark managed to hide two things from the officer, which would become crucial to him as times got tougher. Inside the pocket of his field jacket, Clark hid a tiny note paid he had picked up at an USO canteen. He used this note pad to keep a diary of his captivity and record his thoughts during his ordeal. He also managed to hide a small New Testament." Crawford, John J., Army, captured Dec. 19, 1944 at St. Vith, Stalag 9B, Bad Orb, Interned 104 days, Age 19.