|

American Ex-Prisoners of War

A not-for-profit, Congressionally-chartered veterans’ service organization advocating for former prisoners of war and their families.

Established April 14, 1942. |

|

As a 501(3)c nonprofit organization, American Ex-Prisoners of War is eligible to receive tax-deductible charitable contributions. GuideStar gathers, organizes, and distributes information about U.S nonprofits, and awards its gold seal in recognition of transparency and currency in financial reporting.

|

The Last Christmas in Camp

Christmas in Camp

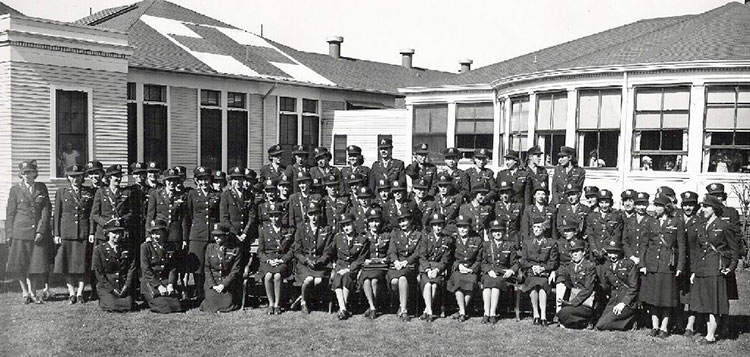

Another in a series of first-hand accounts by POWs of their last moments of freedom and the personal challenges of capture and captivity. These recollections offer poignant and sometimes humorous testimony to the resolve and indomitable spirit of the men and women who fell captive to enemy forces and had to — often in the face of deplorable circumstances — fight for their country in new and unexpected ways. THE BET AT BARTH: A CHRISTMAS STORY by Earl Wasson, ex-POW, 466th Bomb Group, Barth, Germany

In wartime, a place called Barth was Hell. It was a prisoner-of-war camp located only a few miles south of the Baltic Sea in Northern Germany. Downed aircrews were interned there after having been shot down and captured by the enemy. Ten thousand were held there as prisoners. The camp was divided into four administrative compounds with 2,500 airmen in each unit. These "guests of the Germans" were elite quality men&mdashleaders and brave American youths. They had been effective in their aerial combat activity against Nazi Germany. But now, their role had dramatically changed. Internment brought suffering beyond belief; the unending frigid weather, the unpredictable behavior of the guards. Inadequate food, lice, sickness, boredom, death by starvation or by exposure, was their unchanging agenda. Yet there were times when the spirits of the Prisoners of War were lifted. It was always through their own methods of creativity and ingenious that this happened. One ongoing "high" occurred when each new contingent of "guests" arrived in the camp. Up-to-date uncensored information became immediately available. The reports brought in by these new POWs gave fresh, unbiased running accounts of how the war was progressing on both the Eastern Front with the Russians and on the Western Front. The increasing numbers of bombers and fighters appearing in the air overhead brought silent but exuberant joy and hope to Barth's imprisoned. As optimism flourished small group conversation centered on the war's end and their freedom. Liberation was on everyone's lips. The war was indeed winding down! Talk of being home for Christmas became a Utopian Dream. Although all embraced the Dream, not all were equally optimistic. This difference in opinion brought about the "Bet at Barth." A wager was on. New life came to the camp. But what was there to wager!? There was no money, no freedom of 3-day passes to London, no material possessions for the loser to forfeit, no points or promotions to be gained or lost. In a heated conversation two men got carried away in their claims. An optimistic airman bet a pessimistic one on the following terms. "If we aren't home by Christmas, I will kiss your a** before the whole group formation right after head-count on Christmas morning." They shook hands. The bet was on! What the optimist hadn't counted on was the Battle of the Bulge, which took place in early December. Consequently, the war was prolonged and they were still in Barth on Christmas Day, 1944. Christmas morning was cold, there was snow on the ground and frigid air was blowing in off the Baltic Sea. The body count for the compound began, each man was counted off. ein!, zwei!, drei!, vier!, funf!, sechs!, sieben!, acht! Under ordinary circumstances, when the counting was completed and the German guards were satisfied that everyone was accounted for, the group split up and everyone went to their barracks. But this time, everybody stayed in formation. The two betting "Kriegies" walked out of the formation and went into the barracks. No one else moved! The guards were puzzled They didn't know what was going on. Soon, the two men came back out of the barracks. One was carrying a bucket of water in his hand with a towel over the other arm. The second one marched to the front of the formation, turned his back toward the assembled troops and guards, pulled down his pants and stooped over. The other took the towel, dipped it in the soapy water and washed his opposite's posterior. The whole formation was standing there looking and laughing. The German guards and dignitaries of Barth looked on in amazement. They had no idea what was going on. Then the optimist bent over and kissed the pessimist on the rear! A mighty cheer went up from over 2,000 men. Then the puzzled guards joined in the fun. Nothing changed on Christmas day—the same black bread and thin soup, sparse and flavorless. As evening fell, the weather worsened and the barracks grew cold as the last of the daily allotment of coal briquettes were reduced to nothing but white ash. Boredom settled in, and the prisoners anticipated another long, miserable night. Then suddenly the door opened and a voice shouted, "Curfew has been lifted for tonight! We're having a Christmas service over in the next compound." The weather was bitter cold, the new-fallen snow crunched under the feet of the men as they quickly shuffled towards their congregating comrades in the distance. The nightly curfew always kept men inside. This Christmas night's reprieve allowed them to be outside after dark for the first time. Above, the stars were shining brightly high in the northern skies; the dim flicker of Aurora Borealis added a magical touch as the troops assembled. Gratitude was felt in their hearts. A lone singer led out with one of the world's most familiar and loved carols; others joined in, and soon there was joyful worship ringing throughout the camp. Silent night! Holy night!

The German guards marching their assigned beats stopped in their tracks. They turned their heads toward the music. The words were unfamiliar but they recognized the melody—after all, Stille Nacht, Heilige Nacht was composed by a German. They loosened up, began smiling and joined in the celebration; the praise became bilingual. Round yon virgin mother and Child

Holy Infant so tender and mild

Sleep in heavenly peace. Sleep in heavenly peace.

The Bet at Barth had paid off. Everyone had won! As the words of the carol rang in their hearts, there was a literal fulfillment. Tonight they would sleep in peace. War and internment did not have the power to destroy the meaning and beauty of this special day. It was Christmas. They were not at home. But they declared, "Next year we will be! All of us!" And they were!

The Betters Winner: 2nd Lt. Stanley M. Johnson, Port Allegany, PA Loser: 2nd Lt. Richard D. Stark, Tampa, FL Location: North 2 Compound of Stalag Luft I posted 12/19/18

posted 9/25/18

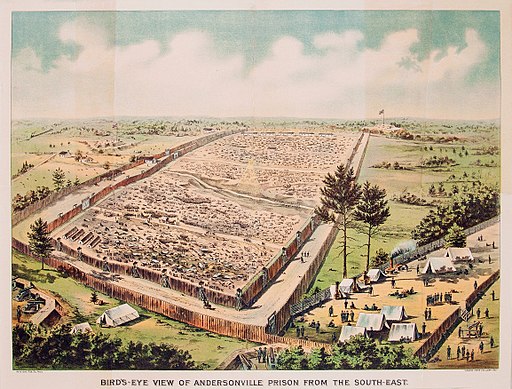

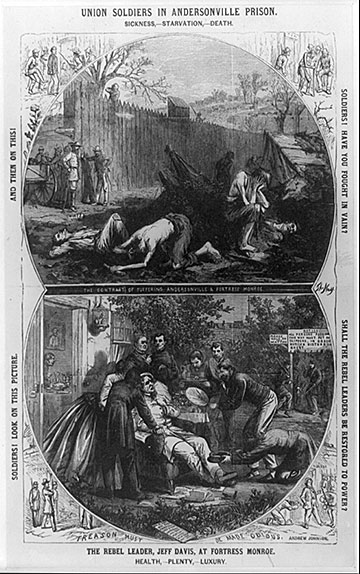

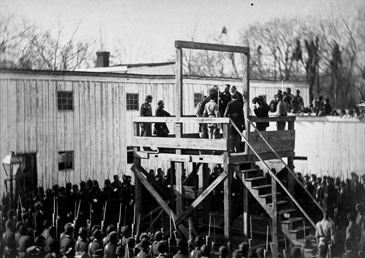

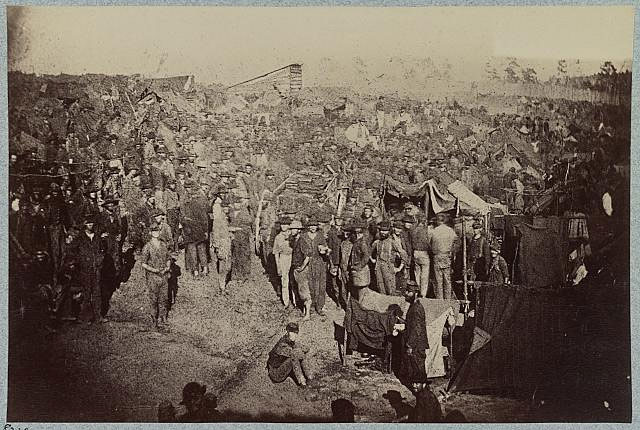

Andersonville Civil War Prison

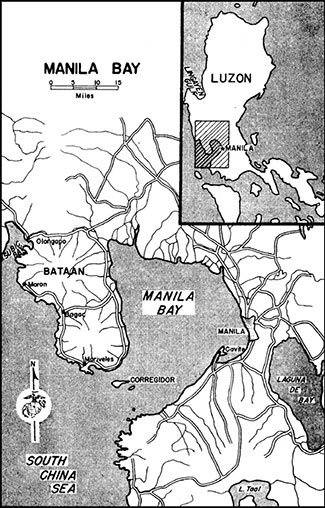

posted 7/13/18 The Angels of Bataan and Corregidor

1967, Maison Centrale, aerial view

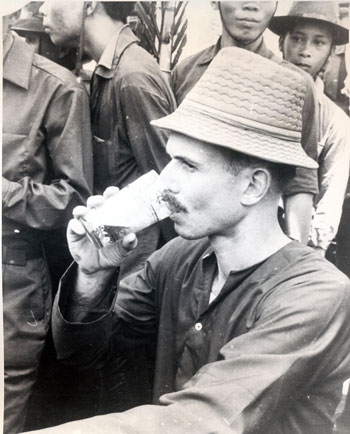

In 1970 a basket of deplorables (Communist Designation) were settling into Cell Seven as part of a massive relocation of prisoners in North Vietnam.

(After the Son Tay Rescue Raid the Communists decided to ship the younger studs up to the Chinese boarder and place us old fuds downtown Hanoi, on ground zero, in case of massive raids and an invasion. American POWs had by then attained a measure of value as hostages.) An Air Force Ace, Jim Kassler (RIP) was at one point regaling me with war stories from Korea and Vietnam. He recounted how just before his shoot-down his crew chief had remarked, while strapping him in to his aircraft: "Don't worry if you get shot down, sir. I understand that they are putting you up in the Hanoi Hilton until the end of the war." Jim allowed as how we might have trouble with that Hotel designation in our dotage. That day in 2017 I feared future generations might consider us to be in the same circumstances as the Saudi Princes currently found themselves — all of us allegedly having been ensconced in the 5-star accommodations of a prestigious hotel chain. Jim predicted revisionist pundits posing as professors, if they should teach about the Vietnam War at all, would manage to remove the quotation marks around "Hanoi Hilton" when referring to the POW main prison location.

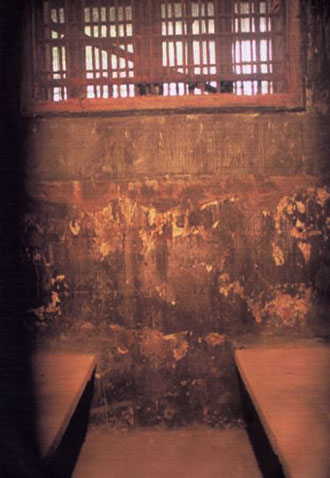

Cell Interior Hoa Lo Prison

In PBS's ersatz 18-hour "documentary" The Vietnam War, Burns and Novick totally distort the Vietnam experience by coating grains or truth with truckloads of misstatements and innuendo. My granddaughters attending colleges and watching TV today are being indoctrinated, not educated. Jim and I started our own reality check by matching stories about our first few weeks after checking to the Maison Centrale. There was no lounge, lobby or check-in area. We were placed in a holding room with knobby walls designed to attenuate sound, a hook in the ceiling and a couple of hooks in the walls. There was one light hanging form a wire out of the ceiling. There was a rusted bucket in the corner obviously for human waste. The surfaces were stained with human fluids. The air was stale, fetid and cloying. I was to spend a week there in my skivvies, "checking in." After about a week in the Knobby Room I was transferred to a private accommodation in the maximum security wing, appropriately named by the old timers "Heart Break Hotel." This cell had hot and cold running rats through a rat hole (drain) at the base of a courtyard wall. I had my own private toilet — a rusted bucket with a lid. There were two cement bed pads built against the wall with leg stocks at the end of each. It appeared to be a space about 6 feet wide, 8 feet long and 14 feet high. There was a bared and boarded window high up on the outside wall and a strong door with a Judas hole on the passageway side. I had two meals a day with random hits on the head and interrogations at unpredictable times through any 24-hour period.

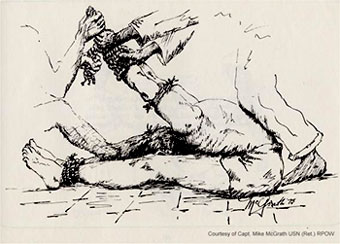

The Strappado in Process: Welcome to Hanoi

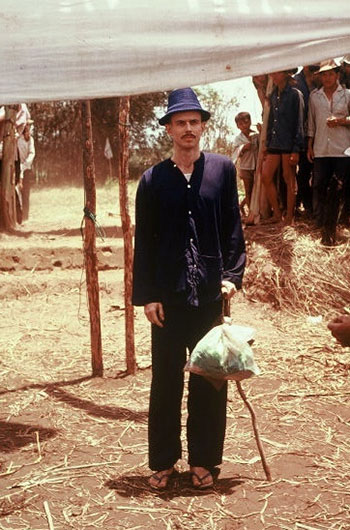

There was no medical care. Once they determined that I was going to live they issued me some go-aheads made of rubber tires for soles and inner tubes for an arch strap, T shirt, skive shorts (boxer), mess dress uniform (striped PJs), a hand towel, a see-thru blanket and a straw matt. I was a thing of sartorial splendor. Interestingly enough, I had no injuries resulting from the blowing up of — and my simultaneous ejection from — the A4E Skyhawk. There were no injuries resulting from the parachute landing or the succession of beatings administered by the rather irate peasants that captured me.

I was unmerciful in critiquing my performance and reaction to the VC — learning from every mistake and becoming aware of every cue as to their upcoming behavior. It was a grand show! I proved to myself while they might be able to control my body they had nothing to say about my mind. They could bend my will but they could not break me. They being the disease, the germs, the pain or the Communists. I could check out any time I wanted to and they wouldn't even know that I was gone.

If you arrived in Hoa Lo with injuries that they exacerbated as part of their torture regime as they did with Jim Kassler and others, torture was an unmitigated evil. Otherwise, if they tortured you, you either lived or you died. Their intent was not to kill you by torture but to exploit you. So voluntary death was not an option that was on the table. As a result you learned how far you could resist on any one day and took the process to that limit. The concept was to bend to just before they broke you and you did something incredibly stupid to hurt your shipmates or your country. You learned that they also had limitations. Authority for torture came from the highest levels and the individual interrogator may or may not have that authority on any one day. They also were working with time constraints and maybe you could outlast them. And sometime, you could make it just too much work for them, given whatever result they were looking for on that day. It was a crap shoot. Eventually I was moved around to other prisons in the Hanoi area: the Zoo, the Plantation, Hoa Lo Little Vegas, and Hoa Lo Unity. At each step the accommodations improved: another cell mate, 3 cell mates, 30 cell mates, 40 cell mates. Torture, as a routine event, stopped around 1969; my last beating was in 1970. I was released in 1973. Food and water became adequate to sustain life. Sporadic mail (6-line forms) exchange was negotiated by Mr. Kissinger. In the fullness of time I won, as had Jim Kassler. After about a year we were of no use to them. They could get no real propaganda value out of Jim the captured"Ace" nor of me"The Mad Bomber of Hanoi." Their efforts to exploit us actually may have done us some good in that they had to produce us or at least account for us at the end of the war. What is the purpose of this discussion? Certainly my wounds were insignificant compared to the horrific combat wounds experienced by the ground troops.

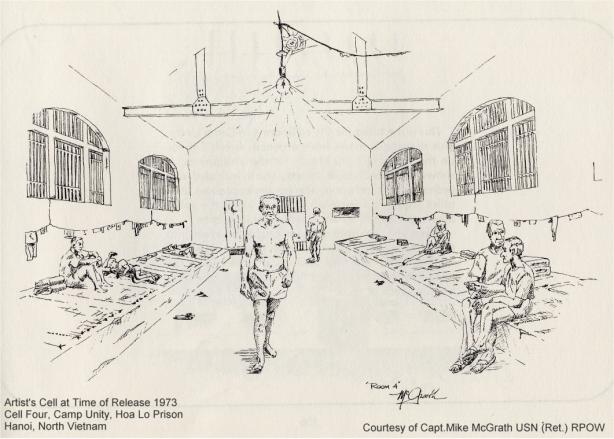

Cell in "Camp Unity section of Hoa Ho

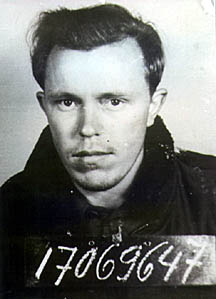

Our living conditions were far superior to those experienced by those captured and held in South Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. I did get to live in the shadow of great Americans: future VP and Presidential candidates, ambassadors, senators, congressmen, politicians, flag & general officers, artists, teachers and captains of industry. I was blessed. The purpose of this discussion is to document two facts. Americans were not treated as Prisoners of War, they were treated as criminals. There was no Hilton Hotel in Hanoi in which prisoners (or princes for that matter) were ever held captive. American POWs were held in the Maison Centrale on 1 Pho Hoa Lo, Hanoi, Vietnam. This jail was sort of a cross between Rikers Island, NYC and Sing Sing in Ossining, NY. The remains of the Maison Centrale are now a museum. Once again, Yogi said it best:"I'm lucky. Usually you're dead to get your own museum, but I'm still alive to see mine." (Thanks to Mike McGrath for the line drawings.) Capt. Richard Allen

Stratton (USN ret) flew 22 combat missions and earned two Air Medals and the Combat Action Ribbon during his service in the Vietnam War. He was attached to the USS Ticonderoga Air Wing 19/Attack Squadron VA-192 as a Lieutenant Commander from 1966-67. While a prisoner of war from 1966 -73 he earned the Silver Star for valor and leadership during his 2,251 days of captivity. From 1989 to 1995 Stratton served as Chairman, Department of Veterans Affairs Advisory Committee on Prisoners of War. Stratton (USN ret) flew 22 combat missions and earned two Air Medals and the Combat Action Ribbon during his service in the Vietnam War. He was attached to the USS Ticonderoga Air Wing 19/Attack Squadron VA-192 as a Lieutenant Commander from 1966-67. While a prisoner of war from 1966 -73 he earned the Silver Star for valor and leadership during his 2,251 days of captivity. From 1989 to 1995 Stratton served as Chairman, Department of Veterans Affairs Advisory Committee on Prisoners of War.posted 4/19/18

Statement of Charles A. Susino, National Director of the American Ex-Prisoners of War, before the Committees on Veterans' Affairs, U.S. Senate/U.S. House Of Representatives, Washington, D.C., March 6, 2018.

AXPOW National Director Charles A. Susino.

Chairmen and members of the House and Senate Veteran's Affairs committee and guests, my name is Charles A. Susino, National Director of the American Ex-Prisoners of War. I am speaking today on behalf of my father, National Commander Charles Susino, Jr. Many of you know him from his previous testimony over the years. My dad joins me in thanking you for the opportunity to express our comments today.

We are grateful for your efforts over this past year. This Congress has stepped up and passed several key pieces of legislation in support of our veterans with respect to health care, compensation, and public awareness in the case of approving a location for the Operation Desert Storm memorial. Your time is scarce and other major Congressional agendas often displace the attention on veterans' needs so we ask for your patience, persistence, and unwavering support. Several pieces of new legislation are important and continually improving all facets of the Veterans Administration operation is necessary. We often speak at this hearing about how the VA needs to improve and model its methods about particular successful and efficient industries. We need to get to where we use the term operational excellence and VA in the same sentence. For an organization that large it takes time, but we need to focus on select areas to build some successes to point at. Our legislative agenda has been very consistent year to year. It is based on the earned benefits of the veteran for serving their country, never using the word"entitlements" in the same sentence as veteran. Its center is healthcare and fair compensation to the veteran and their family. Studies of society conclude the country's population is getting older. That is also true of the veterans as well, especially those that served in WWII, Korea, and Vietnam. The typical WWII veteran is in their 90s along with their spouse and as people are living longer so does our veteran and this creates some unique challenges for the VA. In our organization, we have members in that age group. I am always surprised how little is actually provided for the elderly veterans who are sickly, even those with 100% rating disability. In 1986, Congress and the President mandated VA health care for veterans with service connected disabilities as well as other special groups of veterans. It included veterans up to WWI, some 58 years after the end of the war. WWII ended over 72 years ago. We have asked you for the better part of the last decade to revisit the special groups and update to include veterans of WWII, Korea, Vietnam, Cold War, and our recent conflicts in the Middle East. We have requested for many years with no movement on the part of Congress. With President Trump's support of our military, this President may see it appropriate and fair treatment for those that have kept our country free. We also draw your attention to several bills which we believe have special merit and request your active support. H.R. 27: Ensuring VA Employee Accountability Act. All veterans in all VA facilities deserve adequate care from VA employees. H.R. 4369: To amend title 38, United States Code, to codify the authority of the Secretary of Veterans Affairs to assign a disability rating of total to a veteran by reason of unemployability, and for other purposes H.R. 299 and S. 422 : To amend title 38, United States Code, to clarify presumptions relating to the exposure of certain veterans who served in the vicinity of the Republic of Vietnam, and for other purposes. H.R. 303 and S.66: To amend title 10, United States Code, to permit additional retired members of the Armed Forces who have a service-connected disability to receive both disability compensation from the Department of Veterans Affairs for their disability and either retired pay by reason of their years of military service or combat-related special compensation. S. 339: A bill to amend title 10, United States Code, to repeal the requirement for reduction of survivor annuities under the Survivor Benefit Plan by veterans' dependency and indemnity compensation, and for other purposes. HR 1472 and S. 591: Military and Veteran Caregiver Services Improvement Act of 2017 S. 1990: Dependency and Indemnity Compensation Improvement Act of 2017 S. 544: A bill to amend the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 to modify the termination date for the Veterans Choice Program, and for other purposes. Thank you for your time and attention and most importantly your unwavering support of ex-POWs and all veterans — deserving heroes every one. Charles A. Susino March 6, 2018

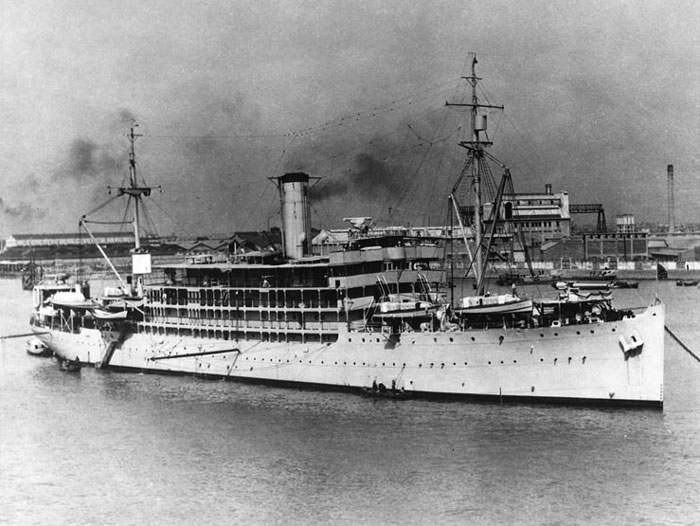

Joint Hearing: Legislative Presentation of the American Ex-Prisoners of War before the House/Senate Veterans Affairs Committees USS Canopus, Star of the Sea

Canopus Awards, Citations and Campaign Ribbons Top Row - Combat Action Ribbon (retroactive - Bataan) - Yangtze Service Medal Second Row - China Service Medal - American Defense Medal (with Fleet clasp) - Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal (1) Third Row - World War II Victory Medal - Philippines Presidential Unit Citation - Philippine Defense Medal

"Submarines are perceived, in popular romantic conceit, as solitary predators that prowl the seas unbounded by time and geography.

In fact they often run in packs, and more often than not those packs are highly dependent on a den mother. No matter where or how far they roam, especially in wartime, subs don't stray too far from the "Mother Ship" and never for too long. They return for all the reasons anyone goes home to mom: for succor, nourishment, replenishment and, often enough, repair. Regardless of the trouble a sub got into or whatever damage it sustained, the mother's job was to make everything all right again, sometimes with remedies bordering on magical. In addition to stores of supplies and munitions, these service ships carried large inventories of parts and materials, and could fix anything. What they didn't have in stock they could make in one of several on-board machine shops. The USS Canopus was one of those ships, in Navy argot a "Sub Tender." She was named for the brightest star in the southern constellation of Carina and the second-brightest star in the nighttime sky. The name itself comes from the mythical figure Canopus, navigator for Menelaus, king of Sparta. She didn't start out as a sub tender. She didn't even start out as Canopus. And she was already long in the tooth when she took her star turn in the Bay of Manila in the early, harrowing days of World War II. She was launched as a passenger liner, the SS Santa Leonora, in 1919 by the New York Shipbuilding Company for W. R. Grace and Co. But her future never lay with the leisure class. She was taken over by the Navy shortly after completion in July 1919 and placed in commission as USS Santa Leonora. She was a trans-Atlantic troop transport briefly but then was transferred over to the Army in September 1919. "Another fire party carried hoses through choking smoke in the compartments near the magazines, pulling the wounded away from blasted areas.

A Shipfitter donned the one breathing apparatus outfit undamaged by the bomb's detonation and carried a fire hose down to the magazines, backed by shipmates working in relays, each of which stayed as long as men could stand the fumes. "The ship's Chaplain led a rescue group into the engine room, where fragments and escaping steam had caused the most casualties, administering the last rites to dying men and helping to evacuate the injured.

USS Canopus (AS-9) in Apra Harbor, Guam, with Submarine Division 17 alongside, October 29, 1924 (US Navy photo).

"The Chief Machinist Mate shut off the steam at the boilers, saving men from being scalded to death, and then helped the wounded to safety. He was later found wandering around the ship in a daze, with no recollection of what happened after the blast."

It took four hours to get all the fires out. In a tour of the magazines several crushed and exploded powder charges were found: unsettling testimony to how close to complete destruction the ship, and all on board, had come. "Only a miracle prevented a general magazine explosion," Capt. Sackett wrote, "but miracles do happen. Bomb fragments had severed several pipes near the magazines, which released floods of steam and water that kept fire away from the rest of the powder." The Canopus was seaworthy again in just a few days, although a good deal of ammunition had been lost when the magazines were flooded, and several store rooms were severely damaged by the explosions.

Between wars: USS Canopus anchored off Shanghai in the 1930s. (US Navy photo)

posted 2/21/18

Wedding Day June 3, 1944. Ft. Charleston AFB

( L to R ) Robert Marker, Ernest Liner, Francis, Julian Ford. "From Charleston our crew went to Westover Field, Massachusetts and flew submarine patrol for two weeks. Then we were given a new plane of our own to take overseas. We left from Mitchell Field, New York and went to Bangor, Maine for supplies, then left the States for Newfoundland where we sat for about a week because of bad weather. "We went on to the Azores when the weather finally broke, and gassed up for the flight to Africa. We landed in Marrakech, then on to Tunis, and from there we flew to Foggia, Italy where they took our plane. They gave us an old beaten up one in its place. Later we found out that this was customary; a new plane was given to a crew that was about finished and ready to go back to the United States "We were assigned to an air base at Cherignola, Italy and given a six-man tent to sleep in at the edge of an almond orchard. At first we had a dirt floor, cots and candles for lights. We started improving the flooring and made some cabinets out of cardboard and rolled up the sides of the tent to let in cool air. After a week or two we were given one bulb for light. It got its power from a generator at the base. "We started flying with other crews to learn how to fly in formation. Experienced pilots flew with us for a few days and then we were on our own to fly every day, weather permitting. We started flying actual combat missions on August 12, 1944. "The targets in northern Italy were called "milk runs," more like training missions, but the Polesti targets were the worst in Europe for enemy flack and fighters. The Hungary targets were bad for fighters, but Blechammer, our target on August 22, was as bad as Polesti. We had to fight our way away from the target until the moment we had to parachute out of the plane. "Before we got to the target we'd lost an engine due to flack (ground fire). We saw one plane blow up and two others take hits. On three engines, we could not keep up with the formation. After the bombs were dropped, we were attacked by four fighters, lost another engine and suffered other damage as well. "One fighter came toward our tail, another from the side, and yet another from the underside. I shot the plane attacking our tail, and it exploded. The fighter on the side killed Tomlinson, our waist gunner, and hit Benetti, the ball turret gunner. That gave the German fighters two positions not covered. "The next attack came from above. Our top-gunner, Peterson, and I both were shooting at him, and he was hit and bailed out. Then I realized we were going down fast and our radio was shot out. I got out of my turret and went up into the waist and put on my parachute. Peterson came down into the waist with his parachute on, and I had to move Tomlinson's body from the escape door so we could get out. I opened the hatch and motioned for Peterson to go out, but he motioned for me to go! I realized that we had to get out, so I jumped. Peterson told me later, when he saw my chute open he jumped, too. "As we were going down, we realized we were being shot at. A German fighter came straight toward me. We had heard about fighter pilots shooting at airmen in their chutes. But, at the last minute this one tipped his wing and came close enough for me to see him motion to me. "I went down in the woods. The others were captured in an open field. I could not get my chute out of the trees, so I took off my flying suit and boots and left them in a stump hole. I crawled under some bushes and tried to collect my thoughts. I removed my escape kit and tried to determine where I was. "I decided to move to a better location but had not gone but about ten steps when someone hollered and I looked to see a German soldier with a rifle pointed at me. He kept motioning for me to put my hands up. I could see he was as scared of me as I was of him. Another soldier then came up, and they searched me. They kept saying "pistols," I guess because they knew we were issued .45 pistols. I told them mine had gone down with the plane. I was always glad that I didn't wear it, because I might have tried to use it. "We were taken to a small village about the size of Efland, North Carolina, and it had a jail. There I saw two of my crew members and four from another crew at the jail. We spent the night with bed bugs androaches. The next day we were moved through the village and were fortunate to have the German soldiers along to keep civilians off of us. They were throwing things, spitting and hollering "gangsters" at us. We understood why later on when we passed a hospital that had been bombed. "We were put on a truck with eight others and transported to the city of Budapest. There we were given something to eat, the first food we'd had had since being shot down. We were questioned and our belts, shoelaces, rings, watches and everything we had in our pockets was taken from us. "We found out later that we were in an old political prison. It was three stories high and was open in the center with walkways around each staircase. All of the cells were solitary cells about four feet by sixteen feet in size with no windows and one light bulb that burned all of the time. Our comforts consisted of one cot, a door with a slot through which bowls of soup were given to us twice a day and one loaf of bread a day, and one bucket for a toilet. No one ever spoke. "Enduring seven days of this, you did a great deal of thinking. I counted the bricks in that cell a thousand times, and I thought I would remember the number, but I don't. After seven days of silence I was taken to a German officer for questioning. We had been trained to give only our name, rank and serial number. I was then sent back to my cell for another seven days, followed by another trip for questioning. "After a few days we were taken under heavy guard to a train station where we were put on those notorious, forty by eight, boxcars that were known all over Germany: forty men or eight horses. "I think there must have been forty of us in the car when more men were brought in. It was too crowded to lie down, so we had to stand or sit. We were locked in our boxcar and in the next one were the guards with their dogs. We only had one bucket for a toilet for over forty men. Some men were sick and some were injured. We were on the train for two days before we were allowed to get out and given water and bread. "At this point everyone was filthy and many had dysentery, still with only one bucket in the boxcar. We stopped in a large rail yard one night and the R.A.F. came over, dropping bombs. The guards left for shelters and we were left behind, locked in the boxcar. Luckily the bombs missed us. They did tear up some of the rails further ahead. We stayed there another day, locked up. Finally, we started again, attached to another train. We started seeing lots of bomb damage to towns and bridges as we passed through Poland. "After five days the train stopped. We were at a train station in a small town where there were guards with dogs to escort us on a one mile walk to our camp. By this time, we were in pitiful shape. The camp was still being built, but we were assigned to barracks with twenty-two men, all together in one room. We had a spigot to wash up with and a latrine which had ten holes. Many times you didn't have time to wait. For that reason it was a very good thing our government sent lots of clothes and shoes to the camps. "We had roll call twice a day, and were given soup and one-fourth of a loaf of sawdust bread a day. Once in a while, we got Red Cross parcels, which were like Christmas to a child. We were each supposed to receive a package, but we usually had to divide one package four ways. They contained everything you needed for a week: canned cheese, canned meat, crackers, candy bars, chocolate, cigarettes, toilet paper (which was worth a fortune), a sewing kit, playing cards, biscuits, and writing paper. "Cigarettes were often used as money; so many cigarettes for a candy bar, so many for a sweater, so many for socks and so many for a pencil. Many old prisoners were getting parcels from home that included clothes, food and cigarettes. We received a variety of things from the Red Cross and the Salvation Army, but it was the food parcels that kept us alive. Many more men would have died had it not been for those food parcels. "We had a number of POW's who went out of their minds and tried to climb the electric wire fences. Guards in the towers would shoot over their heads as a warning but always had to shoot them because they were so determined to try to escape.

"Men in another room had fermented sugar, raisins and other things to make alcohol, and we traded some of our cake for enough alcohol for all of us to have a couple of swigs. The alcohol was very potent, especially on our empty stomachs with that rich cake. Years later there an article about our cake appeared in The American Legion Magazine, December 1957.

"Other men had received musical instruments from home or were able to get the guards to get instruments for them. These musicians would get together and play. At Christmas the Germans allowed us to use a large hall and the men with instruments gave a wild party. You should have seen the crazy dancing that was done. Until the last song, "White Christmas," was played. After that each one of us went back to our room with tears rolling down our cheeks. "We were getting war news from a small radio, the size of a pack of cigarettes, that had been smuggled in a piece at the time. We could receive the BBC once a day on a certain wavelength. One person listened, and told some other men who, in turn, told other men in each of the other barracks to spread the news of the day. "We knew the war was about over and that the Russians were coming toward us. But, we did not know where or how fast until we started to hear big guns in the distance, getting louder. On February 5, 1945, word was sent around to get what you could carry and be prepared to move. Early the next morning, we were marched out the gate in groups of two hundred men, with one guard for every ten prisoners. With every twenty men there was a dog. We went to a warehouse where Red Cross parcels had been hoarded by the thousand and were given all that we could carry. The snow was knee-deep, and the temperature was ten below zero. "We walked about ten kilometers before we stopped for the night in a snow-covered open field. Every one of us was , hungry, thirsty and dead-tired. All that we had to eat or drink was the snow that we could pick up. Many, many nights during the march, we slept on the ground in the ice and snow. Peterson and I each had a blanket and a long Army overcoat made of heavy wool. "We put one overcoat on the ground and covered up with the two blankets and the other overcoat. The blankets were thin like burlap and did not do much to keep us warm. We were not allowed to build a fire even if we had something that we could burn. One morning we awoke to find that someone had switched our top coat and exchanged it for a short one that only went to mid-calf. Our other one went down to my ankles, and was really warm. "Not too long after we started on the march, I had my twenty-fourth birthday, on February 11, 1945. My good buddy Pete (Paul Peterson) presented me with a small piece of bread for my birthday gift. He had saved the bread for me from his small rations for a couple of days. "The next morning we were still tired, had sore, blistered feet and were very hungry. All of us were cold, and some were sick. We had camped by a little stream which we drank from and used as a latrine. We were moved out and went to the road a short distance away and found that another group had used this stream ahead of us! "We walked until almost dark when we reached a school where we had some protection from the outdoors. We had hoped to be able to keep warm inside, but our clothes, shoes and socks were soaking wet. We were warned by some of the older prisoners not to take off our shoes because our feet would swell and our shoes would shrink as they dried. So, we slept in our wet shoes. "If we dared to take off our shoes for the night, we tied the strings together, and put them around our neck for safety. We could not march without shoes. We estimated that we had walked about sixteen kilometers. That night we could hear heavy guns, and British bombers came over and dropped bombs ahead of us. "We started out again the next day. As we had been warned, some men could not get their shoes on because their shoes had shrunk. We were pushed again that day because the guards wanted to get further away from the Russians. Many more men began to drop out and we heard some shooting behind us. We felt that it was probably the guards carrying out their threats. We hardly stopped except maybe to let military traffic go by. " The condition of the men continued to get worse. One night we were able to get into a big barn where we had hay and straw to lay in to keep warm and rest. That barn felt like a motel. We stayed over until the next day and then began another day of walking. We came to another prison camp which was used to get everyone together. "There was every nationality you ever heard of. The French Moroccans had long black hair worn under a turban and they washed it every day under the spigot and took baths out in the open. When they went to the latrine, they carried a little pitcher with water, didn't use paper even if they had it, using instead their left hand. They then washed their left hand and did not use it to eat with. "The young guards were taken away and replaced with old home guards. We actually felt sorry for them but we needed them to keep the civilians away from us. The home guards were getting desperate because they didn't want to be caught by the Russians. One day we were near an old mill sitting in the sun in a cemetery picking off body lice when we heard American bombers. The bombers soon came into sight, straight toward us. They were flying low and we could see bomb doors open. We knew they were getting close to dropping bombs, so we took cover behind a rock wall. Each time a bomb exploded, the wall would start coming apart. It was a very close call for us. We later found out that they were bombing a bridge just beyond us. "By then it was April and getting warmer. We did not have to walk as far, or fast, and found more schools and farms to sleep in. We began to hear more big guns behind us. On the night of April 24, 1945, we were in a big barn when we heard a terrible sound which turned out to be an American armored car coming to find out where we were. "The next morning an American spotter plane came over very low, waving its wings back and forth. We were going toward the Rhine River and later saw two tanks and armored cars with American markings coming toward us. The Americans had stopped at Bitterfield on the Rhine River, waiting for the Russians to get there. We were told they were part of Patton's forward division. We were liberated at Bitterfield on April 26, 1945. The Americans helped us cross the river on a temporary bridge because all of the bridges in the area had been blown up . Peterson and I were taken by a tank crew to a house that the Americans had taken. We were told to burn our clothes, which we gladly did. We had not had a warm bath in two months, had worn the same shoes, had not had a haircut, and were in terrible condition. We both got into the largest bathtub I had ever seen, large enough to swim in. It was wonderful to be able to shave and put on clean clothes. Each of us was given a big glass of whiskey and all of the food we could eat. With full stomachs, we went to bed under a large feather blanket that made us feel like we had died and gone to heaven. "We were trucked to the Hallie staging area and flown to Rheims. We then flew to La Harve on May 13, to Camp Lucky Strike, which had tents for all American POWs. We were fed around the clock and had egg nog between meals. After a few days you would not recognize your friends because they had clean clothes, haircuts, and gained a great deal of weight. Many men got sick from over-eating. "By then the war was over, and we just had to wait for ships to come to take us home. Later we learned that they kept us longer so that we would gain some weight before we got home to our families. We boarded ships on June 5, and docked in New York on June 12. We were then taken to Camp Kilmer, NJ in preparation for going home. You were put in barracks according to the state you lived in. "We were put on a train bound for Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and when we got there we were again examined and given new clothes and $50 to get home. I caught a bus to Fayetteville and then another to Hillsborough. At six o'clock on the morning of June 15, 1945, I walked to my Uncle Ewell's house and he took me home to Franny and the rest of the family. I was finally back home. And thankful." (This write-up by Sgt. Ernest G Liner was taken from the 459th Bombardment Group's website) (Click here for Ernest "Gordon" Liner's full biography posting on this site.) posted 12/23/17 At National World War II Memorial, Veterans Remember the Day It All Started

Veterans of the Second World War gathered Thursday, Dec. 7, 2017, at the National World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C., for a wreath-laying ceremony held in remembrance of the attack on Pearl Harbor 76 year ago.

American Ex-Prisoners of War

Congressionally Chartered

David Eberly Chief Executive Officer

A note to our readers:

At our last convention we could count the returnees and internees on one hand. These veterans served courageously in conflicts that are now simply chapters in the history books. Our heroes—soldiers, sailors, and airmen—are moving on, and their children and grandchildren are the new guardians of our freedom The role that these POWs were called on to play, holding high the torch of liberty for our country and for the world, cannot be allowed to fade away. For our organization, now is the time to turn to the enduring task of keeping the memory alive, relevant and vital. So here at AXPOW our mission is now moving from personal celebration to preservation of a legacy. More than half of our active membership ranks are now Next of Kin members: surviving wives, sons, daughters, grandchildren and other relatives. With time their importance to the organization will only grow. We are tasking ourselves with serving our NOK members' needs by documenting family roots, keeping alive the traditions of POW remembrance and preserving POW histories, narratives and stories in readily accessible forms for future generations. And not just out of filial affection. The work our POWs did helped assure the lives and freedoms Americans still enjoy today. We must not forget what they did because we need to learn from it. AXPOW has no plans to scale back its traditional roles in advocating, counseling and facilitating the efforts of POWs in obtaining medical and financial benefits they are entitled to. And we will continue to champion federal legislation that ensures veterans get the care and treatment they need. Our website has proven a useful tool in pursuing these missions. But going forward this site is gradually giving less attention to organizational news, committees, officer assignments, peripheral service stories and the like and putting more emphasis on developing historical, biographical and contextual resources and feature stories that provide first-person testimony about what POWs endured in captivity and how they endured it.

The prisoner of war experience forms an unbroken chain forged in our national consciousness with links of selfless spirit, enduring will and inextinguishable hope. It connects together all those who have answered the call, whether on the farm fields of Concord, in the mud and muck of Korea, in the Red River Valley of Vietnam, across the sands of the Middle East and among the hills of Eastern Europe. We need to insure that this chain remains strong and intact for future generations—not in dusty volumes or in file drawers but in highly accessible online forms. We want visitors to rediscover the courage and resolve, in the face of deplorable deprivations, of their fellow citizens who fell captive to enemy forces while fighting for their country. Please visit us frequently as we work to keep this story alive and remind America of why it matters. The fact is, today our website's traffic is far broader than our membership. Seventy percent is drawn from the general public. This audience needs to hear our voice as well, to make sure the values that weaned a generation of warriors -- who fought for their country and its legacy not just by force of arms but the strength of their character and the power of their ideals -- are not lost. Why is it so important to say focused on what we must sometimes pay for freedom? Because we need to not just learn about our forbearers' bravery, we need to learn from them how to be brave. In case some future generation is called upon to pay that price again. The future is coming and we are changing to meet it. We hope you will enjoy the journey with us and come back regularly. You are always welcome. Non Solum Armis Sincerely, David Eberly

Statement of Charles Susino, Jr., National Commander/Legislative Officer of the American Ex-Prisoners of War, before the Committees on Veterans' Affairs, U.S. Senate/U.S. House Of Representatives, Washington, D.C., March 22, 2017.

AXPOW National Commander Charles Susino, Jr.

Chairmen and members of the House and Senate Veterans' Affairs committee and guests: My name is Charles Susino, Jr., National Commander of the American Ex-Prisoners of War. Thank you for the opportunity to express our comments today. We are grateful for your committees' efforts in the 114th Congress. However, there is more work to be done to protect our veterans — both on new legislation and improving implementation of legislation already passed. We welcome VA Secretary David Shulkin. We worked well with him in his position as Under Secretary of Health under Secretary McDonald and expect that relationship to continue in his new position. We understand he will want to develop his agenda for the VA however we want to insure that critical initiatives do not get sidelined with the change in administration. A VA directive targeted to eliminate veterans' homelessness has been in effect for several years and results have been positive — an almost 70% decrease in the homeless veteran population. Sadly, however, that means that nearly 40,000 veterans are still on America's streets, without the basic shelter they both need and deserve. The Secretary should report progress and provide a fresh look at proposed actions to achieve this goal. It is a National disgrace that any American veteran has no place to call home. President Trump has instituted a hiring freeze. There is an exception protocol to receive permission for hiring. We ask the Secretary to be both aggressive and vigilant in requesting authorizations to hire for all open positions that are health care service providers to the veterans. The commitment begun under President Abraham Lincoln cannot be compromised. Recently, President Trump stated his commitment in supporting our troops. We accept and welcome his commitment and ask for his support in achieving the legislative agendas of the veterans' service organizations. Actions need to accompany the words to provide the necessary results. Our legislative agenda has been very consistent year to year. It is based on the earned benefits of the veteran for serving their country. Its center is healthcare and fair compensation to the veteran and their family. This level of consistency helps focus our efforts but there is unfinished business. In 1986, Congress and the President mandated VA health care for veterans with service connected disabilities as well as other special groups of veterans. It included veterans up to WWI. We ask Congress to revisit the special groups and update to include veterans of WWII, Korea, Vietnam, Cold War, and our recent conflicts in the Middle East. A common thread among the veteran service organizations has been improving the performance of the VA. Last year at this time, we publicly stated that we supported Secretary McDonald's efforts to change the VA culture and reorganize to obtain better access, treatment experience, and understanding for the veteran without compromising efficiencies and accountabilities. The Secretary outlined to you his plan to transform the VA into a high performance organization. It was based on changing the VA culture and reorganizing to obtain better access, treatment experience, and understanding for the veteran without compromising efficiencies and accountabilities. We are anxious to hear from Secretary Shulkin outlining his initiatives and any changes he determines are required to achieve the goals necessary to best serve our veterans. We realize it is challenging, but the changes must start at the top and get to where the veterans' experience occurs in the near future. To achieve the needed results in the VA the rules need to change. The VA needs to broadly adopt management policies to facilitate the culture change required within the VA. There are several Bills that partially address the issue but it must be broad in nature and provide management latitude but require a high level of accountability. Any single Bill on the management bonuses, employee discipline, etc. is insufficient. It must mirror HR policies of select businesses where achievement is high in efficiency and accountability therefore a comprehensive Bill is needed to achieve the desired result. In addition as I stated last year, DIC has not been increased, aside from COLA, in decades and we ask for your support to correct this longstanding inequity. I draw your attention to the following Bills that are strongly supported by the American Ex-Prisoners of War: H.R. 104: Helping Homeless Veterans Act of 2017, to make permanent certain programs that assist homeless veterans and other veterans with special needs H.R. 333: Disabled Veterans Tax Termination Act, permitting veterans with a service-connected disability of less than 50% to concurrently receive both retired pay and disability compensation H.J. Res. 3: Approving the location of a memorial to commemorate and honor the members of the Armed Forces who served on active duty in support of Operation Desert Storm or Operation Desert Shield H.R. 544: Private Corrado Piccoli Purple Heart Preservation Act, to provide for penalties for the sale of any Purple Heart awarded to a member of the Armed Forces. H.R. 369: To eliminate the sunset of the Veterans Choice Program, and for other purposes S. 24: A bill to expand eligibility for hospital care and medical services under section 101 of the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 to include veterans who are age 75 or older. During this election year, there have been calls from some candidates to shift VA from its primary role of directly providing care to that of simply paying outside providers in order to control costs and manage service. We ask that Congress not waiver from its responsibility to protect any intrusion that threatens the promises made to those heroes who serve their country. While the VA may be cumbersome and unwieldy, it offers the best care for our veterans in terms of efficiency and quality of service. VA providers have walked the "mile in their shoes" as veterans themselves. With respect to funding Memorials, it is gratifying to hear the progress of the WWI memorial and others. We encourage Congress to continue to fund public awareness initiatives. It is a critical component of public awareness and education on the hardships of war. As time passes, there are less and less of us that experienced first-hand how life in our country changed in support of a large scale war. While we need to protect our freedoms we also must remember the cost of freedom is very high. Please eliminate the veterans' means test for access health care. Should a veteran who worked two or three jobs to provide better for his family later be deprived of healthcare? Each has served his country and earned the same benefits so let us not deprive any deserving veteran of healthcare. It is most insulting to us when we hear the use of the word entitlements regarding any benefits to the veteran. These are all earned benefits where the veteran has served and sacrificed. Calling them "entitlements" relegates the program to a handout and needs to be eliminated from the language used for veterans. Thank you for your recent efforts in the last Congress. There were many accomplishments and without your leadership none of it would have been possible. Please continue your tireless work. Thank you for your time and consideration on these matters. God Bless Our Troops Charles Susino, Jr. March 22, 2017

Joint Hearing: Legislative Presentation of the American Ex-Prisoners of War before the House/Senate Veterans Affairs Committees The Bloody Battle of Iwo Jima and the Timeless Images That It Spawned

Sixty-third Annual Veterans Day National Ceremony — Arlington, Nov. 11.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![The homes of Andersonville, 1890. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2006683515/. The homes of Andersonville, 1890. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress](images/andersonvillehomes.jpg)

Regiment's 4th Battalion Reserves (Provisional), which fought the final battle for the island fortress.

Regiment's 4th Battalion Reserves (Provisional), which fought the final battle for the island fortress.

recorded the first flag-raising, an act that greatly inspired the American soldiers fighting for control of Suribachi's slopes.

recorded the first flag-raising, an act that greatly inspired the American soldiers fighting for control of Suribachi's slopes.

most reproduced photograph in history and won Rosenthal a Pulitzer Prize.

most reproduced photograph in history and won Rosenthal a Pulitzer Prize.

heavy artillery fire and suicidal charges from Japanese infantry.

heavy artillery fire and suicidal charges from Japanese infantry.