Established April 14, 1942

|

American Ex-Prisoners of War

A not-for-profit, Congressionally-chartered veterans’ service organization advocating for former prisoners of war and their families.

Established April 14, 1942 |

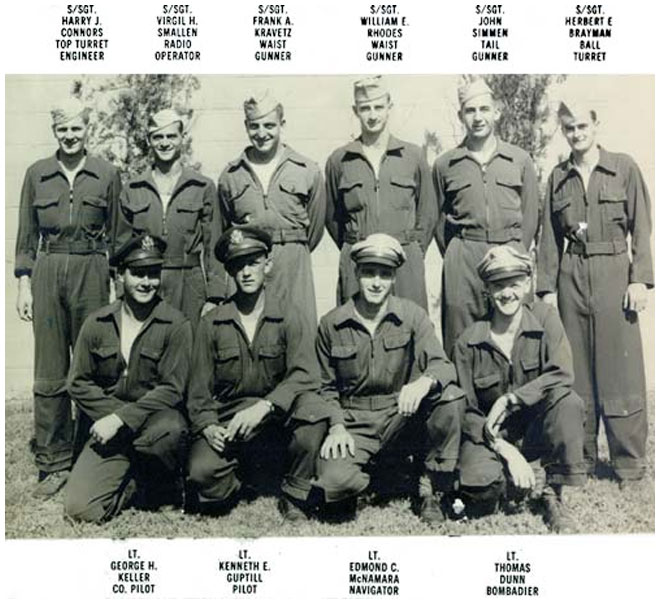

1944 Service Photo

|

Frank A. Kravetz, Baton Rouge Nat. Convention 1998

|

Relaxed Moment 1944

|

| Last Name | First Name, Middle Init. | Nickname |

| Spouse | City | State, Zip |

| Conflict — Theatre | Branch of Service | Unit: |

| Military Job | Date Captured | Where Captured |

| Age at Capture | Time Interned | Camps |

| Date Liberated | Medals Received | |

| After the War ... | ||

He had been a POW since Nov. 2, 1944 when his B-17 bomber wend down over Hanover, Germany. When he had first reached the hospital, set up in an old school, conditions were bearable. But by Christmas Day, 1944, the hospital was jammed with new patients, most of them young American soldiers wounded and captured in the Battle of the Bulge, Hitler's last-gasp effort to turn the tide of World War II in western Europe.

Then the hospital was overwhelmed with patients. The newly wounded were laid on stretchers on the floor between the bunks. Supplies of food and medicine were running low. "In fact, you had guys literally dying left and right," Kravetz remembered. The new patients brought with them devastating news. Prior to Hitler's massive winter offensive, launched Dec. 16, 1944, it was widely believed that Allied forces would quickly bring Germany's war machine to its knees. But information brought by the new patients dashed any hopes that the Nazis were ready to quit fighting. "The Germans were overrunning our troops," Kravetz said.

Red Cross packages arrived in time for Christmas. Kravetz received a pipe and took tobacco from cigarettes to smoke it. Pitchers of beer were provided, and the Germans arranged for a midnight Mass to be celebrated in Kravetz's ward. Still, news of Germany's surprise offensive, which caught Allied commanders off guard, over-shadowed the gifts. "Our morale at the hospital really went to a low ebb," Kravetz admitted.

|

|

Photos during my internship! |

|

"When we were attacked, I was wounded in both legs by shrapnel from enemy gun fire. We kept the plane airborne long enough to make it to Hanover, were we had to bail out from a flak attack. When we were bailing out my chute opened in the plane. My crew members folded my chute in my arms and me dragged to the door."

Shrapnel from the fighter's cannons tore apart Kravetz's legs. Two of the B-17's engines were knocked out. Crewmembers ditched extra ammunition and equipment to lighten the plane. Kravetz, who was slipping in and out of consciousness, was dragged from the tail to the waist section of the aircraft. As the bomber limped along at an altitude of between 5,000 and 6,000 feet, enemy anti-aircraft gunners zeroed in on the crippled plane. "We were sitting ducks at that time. We were pretty low so our pilot dipped the wings (a signal that the crew wanted to surrender) and ordered us to bail out," Kravetz said.

Kravetz's fellow crew members treated his wounds with sulfur powder and compresses. After giving him morphine, they strapped him into a parachute harness, rolled the cloth chute into a ball, and placed it in their wounded buddy's arms. Then they tossed Kravetz out of the plane.

"I was conscious all the way coming down in the parachute. In fact I noticed it was 2:10 in the afternoon because I had my watch on" Kravetz said. He landed in a cabbage field where he managed to wriggle out of the parachute and give himself an injection of morphine. German civilians, set on retribution, spotted Kravetz. However, German soldiers interceded. "They fired some rifle shots in the air to scare off the civilians. They (the civilians) probably would have abused me and everything else" Kravetz said. "I just took my .45 out of my holster and I held it out in a non-threatening position," he remembered. "I wasn't going to offer any resistance to them. What I needed was a lot of help because I wasn't going to move anywhere for a long time."

"Shortly after landing in a cabbage patch I was taken to a barn, and I was there until I was taken to a hospital in Hanover. (it seemed like days because of a loss of blood and shock). After an operation in my legs I was taken to Dulag Luft on Nov. 11, 1944, then to Obermassfield for more operations, skin grafts, and rehabilitation.

The solders took Kravetz's wallet, personal photos, watch and jewelry. "Then they waited awhile. Someone went and found part of a fence and they used that as a stretcher to carry me to the road," he said. Kravetz was loaded onto a farm cart. As he was being wheeled down the road he saw another crewmember being escorted by soldiers. It was Bill Rhodes, a waist gunner who now lives in Madison, Wis. "Bill's face was all battered, bloody and everything else," Kravetz recalled. "I asked him, what happened to you?" He said, "They beat me." If you were wounded, "I guess they had some sympathy toward you, which was my case," he added.

"At that point I thought surely they were going to amputate my left leg because it was turning black," Kravetz said, but a German surgeon saved the limb. Hanover's rail yards and train station were the targets of air raids by British and American planes. During the raids, Kravetz remained in bed instead of being taken to an underground shelter. "Windows would shatter. Glass would fly. Beds would jump and everything else, it was just a horrible time to be alone. It would have been different if I had somebody with me to communicate with. I didn't have anybody," Kravetz said.

From Hanover, he was taken to the hospital staffed by the Allies in Obermassfeld. By the end of January 1945, Kravetz was scheduled to come home on a Swedish repatriation ship. But after the Battle of the Bulge "There were a lot more higher priority people so I went way down on the list," he said. He was sent next to a POW Camp called Stalag XIIID. After several weeks, he and other captives embarked on a 15-day forced marched to Stalag VIIA in Moosburg, Germany.

"In the middle of February I arrived in Nuremburg and was there until April 1 when we left by foot for Mooseburg (approximately 150 kilometers). We got there on April 15, and were liberated on April 29th.

Prisoners were given the option of walking or traveling by train to Moosburg. "I and a lot of the other fellas said, "Let's walk, because you're taking your life in your hands by going by train, everybody is strafing trains." They weren't putting any markings on them (train cars) to signify that they were carrying POWs" Kravetz said.

The march was difficult. "When you did stop to sleep, you slept in barns or under any kind of roof, whatever the Germans gave you. Or you just huddled together with someone else in the woods and just tried to sleep," he explained. American forces liberated the Moosburg Camp on April 29, 1945. By then, Kravetz -- who at the time of his enlistment had to lose weight to come in under the 175-pound limit -- weighed just 125 pounds.

"I remember the Stars and Stripes going up over the barracks, the swastika coming down" Kravetz recalled. "(U.S. Gen. George) Patton came in and told us, "Everybody stay put. Don't go roaming around the countryside because there are mines around. You fellas aren't in any kind of shape to be traipsing around a lot." For the first time in months, Kravetz ate a slice of white bread. The liberated POWs were also treated to hot chocolate. "It made guys sick because it was too rich for them," Kravetz recalled.

Kravetz hopes to return to to Moosburg to observe the 50th Anniversary of the liberation of the POW Camp next summer.

(from "POW Recalls Wartime Christmas," by Martin Kennunin, Pittsburgh Tribune Review, 1998.)